Educator Tools

Ask yourself:

Ask yourself:

- To what extent has Canada fulfilled its human rights obligations to Indigenous people?

- What actions are Indigenous people taking to advocate for their rights?

- Why did the government of Canada remove children from First Nations, Métis and Inuit families and force them to live in residential schools?

Definitions

Definitions

The terminology used in Canada to refer to Aboriginal Peoples has evolved over time. First, the term Aboriginal was used when referring to First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples. In 1982, this term was used in the Constitution Act. Section 35 (2) of the Act states: In this Act, “aboriginal peoples of Canada” includes the Indian, Inuit and Métis peoples of Canada. At the present time, the federal government uses the word indigenous instead of aboriginal; however, the provinces use a mix of the two terms.

In Canada, there are three groups of Indigenous people:

The First Nations are made up of over 630 distinct bands with the majority living in Ontario and British Columbia

The Inuit inhabit the northern regions of Canada

The Métis originated in the 1700s when French and Scottish fur traders married Aboriginal women, largely from the Cree and Anishinabe (Ojibway) peoples. Alberta has the largest Métis population.

Today there are about 370 million Indigenous Peoples found in 70 countries. In almost all these places, the Aboriginal populations suffer from lack of representation in government, poverty, poor access to social services, and discrimination.

ACTION 1

Discuss

Discuss

How are the lives of Indigenous Peoples across the world affected by each of the following?

| Lack of Representation in Government | |

| Generational Poverty | |

| Lack of Access to Social Services | |

| Discrimination |

FIRST NATIONS’ RIGHTS IN CANADA TODAY

In October 2013, the United Nations sent investigator James Anaya to research the condition of Aboriginal human rights in Canada. Anaya said one in five indigenous Canadians live in dilapidated and often overcrowded homes and “funding for Aboriginal housing is woefully inadequate.” He said the suicide rate among Inuit and First Nations youth living on reserves is more than five times greater than that of other Canadians. One community Anaya visited had suffered a suicide every six weeks since the start of the year. Anaya said such problems persist even though Canada was one of the first countries to extend constitutional protection to the rights of Indigenous p,eople, has taken notable steps to repair the legacy of past injustices, and has developed processes for land claims “that in many respects are models for the world to emulate.” Anaya encouraged the government “to take a less adversarial” approach to land claim settlements “in which it typically seeks the most restrictive interpretation of aboriginal and treaty rights possible.”

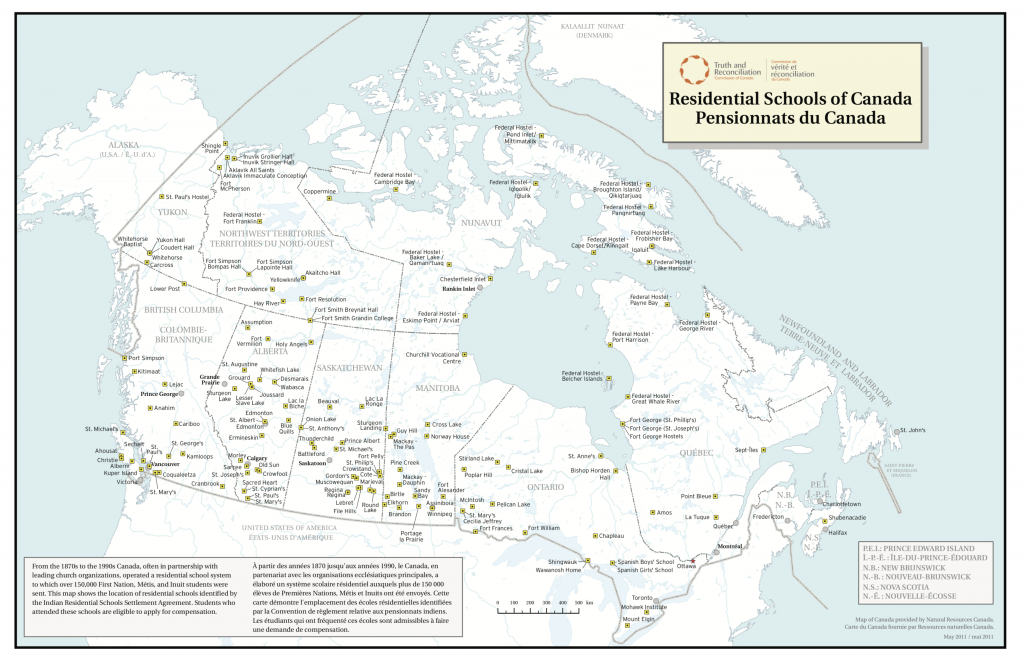

A Brief History of Residential Schools (1880s – 1996)

Indigenous people are the first people to arrive and settle in a territory. When European explorers and settlers arrived they found vast numbers of Indigenous peoples living in the Americas. There were the empires in Peru and Mayan city-states. In what we now call Canada there were confederacies such as the Five Nations, (the Iroquois or Haudenosaunne were part of that confederacy), chiefdoms like the Haida and Kwakiutl, and small band communities of mobile hunter/gatherers (the Huron or Wendat and the Cree).

This really happened

Indigenous people died from European diseases, for which they lacked immunity, and were subjugated by the policies enacted by European settlers and immigrants. By the time Canada had established itself as a confederation in 1867, Indigenous communities were reduced in number and occupied only a tiny fraction of their ancestral lands. English and French immigrants took control of those lands and formed a government without the participation of the Indigenous people. The Canadian government began to question what to do about Indigenous people who were now considered a problem that needed attention.

One idea was to use education as a way to assimilate Indigenous children into Christian European society. It was hoped that eventually all these people would be assimilated and become Canadian citizens without retaining their Indian heritage. This process would strip them of their culture, languages, traditions, and spiritual beliefs.

The Indigenous Peoples of Canada were considered by many to be childlike and culturally inferior. The government believed that the best approach to reach the goal of assimilation was to take children from their parents and immerse them in schools that taught the elements of European/Canadian culture. In the 1800s, one Canadian politician summed up these beliefs when he said that the objective of the Residential School policy was to continue until there was not a single Indian left in Canada that has not been absorbed into the larger culture.

Residential Schools were run by the Canadian government in partnership with various religious groups. Catholic, Anglican, Methodist, Presbyterian, and United churches became the administrators of the schools. Religious organizations believed that it was their duty to bring Indigenous children into the Christian faith. Generally, children were taken from their parents around the age of four and continued in the Residential Schools until the age of 16. They returned to their parents each summer for two months and were forbidden to speak their own language. Parents were fined or jailed if they did not send their children to these schools where the education was often substandard. Many schools focused on teaching tasks that would enable the children to become manual labourers or service providers. Over 40% of the teachers in Residential Schools were not professionally trained.

We know from those who attended Residential Schools that many lived in difficult and substandard conditions. The food was not nourishing and was sometimes even rotten. Children suffered physical abuse, which some teachers believed was essential to “civilize” them. Many testimonies about sexual abuse in Residential Schools have been recorded by male and female survivors.

Gordon’s Indian Residential School (1888-1996)

The Gordon’s Indian Residential School (mentioned in the video with Warren Burton Green) was managed by the Anglican Church of Canada from 1876 to 1946. Gordon’s was later managed by the Indian and Eskimo Welfare Commission from 1946 to 1969, and by the Government of Canada from 1969 until its closure in 1996. The Anglican Church continued to provide chaplaincy into the 1990s.

ACTION 2

Think

Stop and think

- Why did the Government of Canada take First Nations, Métis and Inuit children from their parents to live in Residential Schools?

- What was the impact of Residential Schools on the families and traditions of Indigenous people?

- What is the Canadian government doing to address the effects of Residential Schools?

The Effects of Residential Schools on Indigenous Culture

“When an Indian comes out of these places it is like being put between two walls in a room and left hanging in the middle. On one side are all the things he learned from his people and their way of life that was being wiped out, and on the other side are the white man’s ways which he could never fully understand since he never had the right amount of education and could not be a part of it. There he is, hanging, in the middle of two cultures: he is not a white man and he is not an Indian.”

– John Tootoosis, Cree leader and former student at the Demas (Thunderchild) Indian Residential School, Demas, Saskatchewan

Seven generations of Indigenous people went through Canada’s Residential Schools. Life in the schools impacted children who lived in them in ways similar to the way Post Traumatic Stress symptoms affect some combat soldiers. In most families, the impact of this trauma was passed down to the next generation. Children taken from their homes at an early age had no concept of family to pass on to their own children and they lacked proper parenting skills because they were not properly parented away from their families.

As they grew up, some people developed a dependence on drugs and alcohol in an attempt to numb their pain and forget their traumatic and abusive experiences. People also failed to encourage their children to pursue education given their own experience in Residential Schools. The long list of effects of physical and sexual abuse suffered by those who were victims of Residential Schools has led to multi-generational trauma. Many First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities are now developing systems to work with several generations of families and the survivors of Residential Schools are being encouraged to tell their personal stories.

Political Response and Responsibility—How the Government of Canada is Addressing the Effects of Residential Schools

In early 1998, 79,000 Residential School survivors sued the Canadian government for compensation for their suffering in the Residential Schools. As a result of this action the government agreed to financial compensation for the survivors, and they also agreed to the establishment of The Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. The mandate of this commission is to make sure that all Canadians are aware of the experiences of children in the Residential Schools and the impact of those experiences on the survivors, their families, and future generations. The commission, supported by the government, encourages survivors and their families to come forward and to tell their stories so they can be documented. The telling of the stories of survivors is seen as a part of the healing process for the victims but Canada as a nation cannot move forward until these stories are documented.

The following quotation is taken from the formal apology made by Prime Minister Stephen Harper on behalf of the Government of Canada for the harm caused to many generations of First Nations, Métis and Inuit families by the Residential Schools. It was delivered in the House of Commons on June 11, 2008.

“For more than a century, Indian Residential Schools separated over 150,000 Aboriginal children from their families and communities. In the 1870s, the federal government, partly in order to meet its obligation to educate Aboriginal children, began to play a role in the development and administration of these schools. Two primary objectives of the Residential Schools system were to remove and isolate children from the influence of their homes, families, traditions and cultures, and to assimilate them into the dominant culture. These objectives were based on the assumption Aboriginal cultures and spiritual beliefs were inferior and unequal. Indeed, some sought, as it was infamously said, “to kill the Indian in the child”. Today, we recognize that this policy of assimilation was wrong, has caused great harm, and has no place in our country.”

In September 2013, Indigenous communities held a Walk Across Canada. This Residential School Reconciliation Walk ended a week-long Truth and Reconciliation Commission event. All people were encouraged to attend the march that hoped to promote healing by gathering and sharing stories and expressing a commitment to move forward.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada completed its reports in 2015. Links have been provided below to documents like The Survivors Speak. Here is an excerpt:

A Survivor is not just someone who “made it through” the schools, or just “got by” or was “making do.”A survivor is a person who persevered against and overcame adversity. It came to mean someone who could legitimately say “I am still here!” For that achievement, survivors deserve our highest respect.

The reports of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015 offer the following for public use:

Honouring the Truth: Reconciling for the Future

What We Have Learned, Principles of Truth and Reconciliation

The Inuit and Northern Experience

Canada’s Residential Schools: Missing Children and Unmarked Burials

Canadians acknowledge that the Residential School system promoted the destruction of Indigenous culture and society–a significant part of the foundation of Canada’s multicultural environment.

In 2021, unmarked graves were discovered on the grounds of multiple Residential Schools across Canada and are believed to be the graves of children who attended the schools. Today, the search for the remains of children who died of disease and neglect or who may have been killed at the schools is ongoing across the country. Orange Shirt Day on September 30 is a time for Canadians to reflect on this history and to remember that Every Child Matters.

ACTION 3

Discuss

Listening to History

- Why do you think some survivors did not want to tell their stories to the commission?

- What supports would you provide to survivors to help them heal?

- Should the government and the churches that ran the schools be punished in some way for the actions of the staff in Residential Schools?

- Should the Muscowequan (Muskowekwan) Indian Residential School building be preserved as a memorial to the victims and for ongoing public education about the era of Residential Schools in Canada?

According to the Legacy of Hope Foundation, “From the early 1830s to 1996, thousands of First Nation, Inuit and Métis children were forced to attend Residential Schools in an attempt to assimilate them into the dominant culture. Those children suffered abuses of the mind, body, emotions, and spirit that are almost unimaginable. Over 150,000 children, some as young as four years old, attended the government-funded and church-run Residential Schools. It is estimated that there are 80,000 Residential School survivors alive today.”

Learn about the Muscowequan Residential School

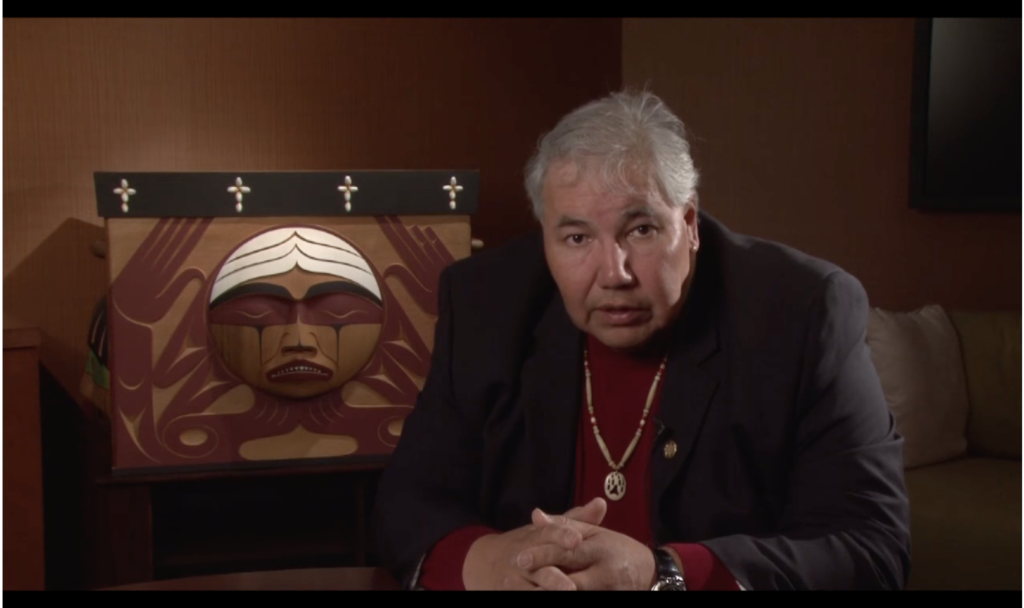

Watch Murray Sinclair Discuss Reconciliation

Justice Murray Sinclair chairs the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, part of a comprehensive response to the Indian Residential School legacy. The Commission’s mandate is to inform all Canadians about what happened in Indian Residential Schools and document the truth of survivors, families, communities and anyone personally affected by the Indian Residential Schools experience.

Sinclair is Anishinaabe and a member of the Peguis First Nation. He is a Fourth Degree Chief of the Midewiwin Society, a traditional healing and spiritual society of the Anishinaabe Nation responsible for protecting the teachings, ceremonies, laws, and history of the Anishinaabe. His Spirit Name is Mizhana Gheezhik (The One Who Speaks of Pictures in the Sky).

The Sixties Scoop

Indigenous Canadian children were removed from their birth families to adoptive homes from 1961 to the 1980s. Often without parental and band consent, children were adopted across Canada, in the US and Europe, into mostly non-Indigenous middle-class families. This experience left many adoptees with a lost sense of cultural identity. The physical and emotional separation from their birth families continues to affect adult adoptees and Indigenous communities to this day.

On June 18, 2015, the Province of Manitoba issued an apology for the Sixties Scoop and announced that this history will be included in school curricula. On February 1, 2017, the Canadian government announced that it was ready to negotiate a settlement to the $1.3 billion class-action lawsuit launched against it in 2009. On October 6, 2017, the federal government agreed to pay $800 million as compensation to victims of the Sixties Scoop. The settlement will go to approximately 20,000 victims across Canada who will be paid between $25,000 and $50,000 each.

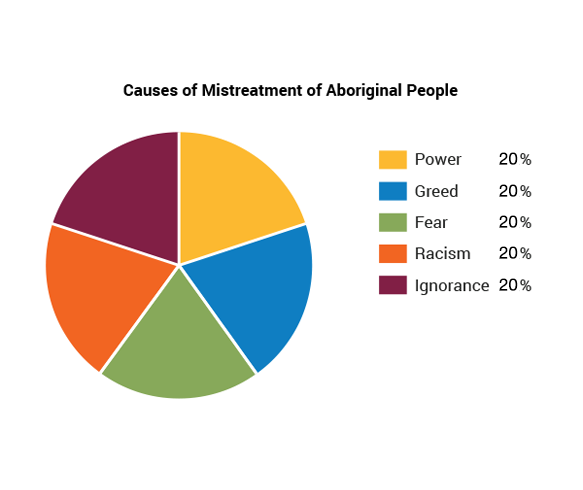

Based on what you have learned thus far and your own experience of conflict, work in a group to create a pie graph that shows how much each of the following elements caused this mistreatment of Indigenous people: Power, Greed, Fear, Ignorance and/or Racism.

Example of pie graph with sample percentages (your values will be different and should total 100%).

Sources:

1. Legacy of Hope

2. Canada’s First Nations, A History of the Founding Peoples from Earliest Times, par Olive Patricia Dickson avec David T. McNab, Oxford University Press, quatrième édition, publié en 2009.

Be ready to explain why you gave the values you did to each of the five components. As you learn more about Canadian history, take note of any changes in your attitudes and opinions.

ACTION 4

Think

Hungry Canadian Children were used in Government Experiments

The Toronto Star, reporting on the research of nutritional scientist, Ian Mosby, wrote that “For over a decade, aboriginal (sic.) children and adults were unknowingly subjected to nutritional experiments by Canadian government bureaucrats.”

“Aboriginal children were deliberately starved in the 1940s and 1950s by government researchers in the name of science. Milk rations were halved for years at Residential Schools across the country. Essential vitamins were kept from people who needed them. Dental services were withheld because gum health was a measuring tool for scientists and dental care would distort research.”

Reading through Rationalizations and Justifications

As you read the Toronto Star article on Hungry Canadian Aboriginal Children ask yourself how the scientists at the time could possibly justify what they were doing. When you finish reading, discuss with your group answers to the following questions:

- Why would Canadian scientists and organizations like the Red Cross participate in this kind of experimentation on children?

- What reasons does Mosby give for the compliance with this research?

- What do you think would have happened if the Red Cross had suggested doing this research at an expensive private boarding school instead of a Residential school?

How was this injustice rationalized?

Mosby believes that the existence of this research has remained hidden for the following reasons:

- In addition to the fact that there were problems with some of the studies’ methodologies, they were not cited in journals and were therefore forgotten.

- The researchers felt they were not doing anything wrong.

Which of these reasons do you think was most important?

What other reasons might there be for this research to remain hidden?

Why might it be important for this research to be known to the public?

Are there problematic ideas that underpin Western science that facilitate abusive research experiments?

How important is the news media in protecting the human rights of individuals?

Who controls what is reported in the news?

Which rights outlined in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child have been abused by the researchers?

What agencies are available today to protect children in Canada who feel that their rights are being abused?

ACTION 5

Do

Visual Reading

Image of Senior Classroom, Residential School

Credit: General Synod Archives, Anglican Church of Canada

This photograph shows a classroom in a First Nations Residential School. Look at the faces of the students in this class. Look at their posture. What can you learn from looking at the picture?

Use the following chart to guide you:

| Question | Reasons for your inferences |

|---|---|

| Who is in the picture? | |

| Where was this picture taken? | |

| When was the picture taken? Who might have taken it? | |

| Who was the intended audience for this picture? | |

| What was the photographer’s message about the content of the picture? |

ACTION 6

Do

Make Connections!

- Move around the classroom and share your picture with other students.

- Talk to three people with the same picture and at least three people with different pictures.

- Make predictions! How might your photo relate to someone else’s? Does your photo connect to an idea already studied in class? How is your snapshot different from the others?

- Share your inferences and connections with your classmates.

- Record your inferences. Complete the AFTER section of your organizer by explaining what you learned from the discussions and the connections you made.

- Check the chart you have made to see if you want to change any of your first inferences.

ACTION 7

Do

Create a Newspaper Article

You are a reporter working for a newspaper on a series called “The True Story of Residential Schooling.” The pictures you’ve discussed tell one story of Residential Schooling but the editor of your paper feels that the pictures do not tell the whole story of Residential Schools. She wants her reporters to explore the stories the pictures don’t tell.

Choose from the list below, and rank in order, three people who will tell you their story of Residential Schooling.

- An Inuit woman in her 70s who was at a Residential School for five years from the age of four.

- A woman aged 80, of European ancestry (not religious) who taught at a Residential School for fifteen years.

- A priest responsible for a Residential School for ten years.

- A First Nations man whose father, now dead, attended a Residential School for ten years.

- A First Nations woman who attended a school with her sister who died at the school.

- An Aboriginal Elder who has been counseling members of her nation who attended Residential Schools and consider themselves survivors.

- A male teacher of European ancestry who taught shop and coached the hockey team at a Residential School.

- The doctor who was occasionally called in to see to the health of children at the school.

Explain why you chose the people you did.

Of three people, choose one to interview for the paper. Prepare five compelling questions to ask in your interview.

Go to the Legacy of Hope Foundation website to find out as much as possible about what Indigenous people say happened at the Residential Schools.

Choose one section of the website, or some other information you have found in your research that you want to share with the class.

Every Child Matters

“Every Child Matters” is the Orange Shirt Day slogan, meaning that all children are important – including the ones left behind and the adult survivors who are still healing from the trauma of Residential Schools.

Further Resources

Program interviewing Ian Mosby, food historian

Experiments on Aboriginal Children

Toronto Star editorial

Canada Admits Abuse

Opinion piece by Phil Fontaine, Bernie Farber and Dr. Michael Dan in Toronto Star

Genocide of First Nations

Ipperwash Provincial Park and the contestation of ancient burial grounds.

Ipperwash Crisis

The Idle No More movement

Idle No More Story

Idle No More Movement

National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation

Residential School History

Timeline of Residential Schools – the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

The Seven Sacred Teachings of White Buffalo Calf Woman

ayisiyiniwak A Communications Guide

Every effort has been made to gain permission from copyright holders to reproduce borrowed material. The publishers apologize for any errors and will be pleased to rectify them in subsequent reprints and website programming.

Educator Tools