Educator Tools

Key Questions:

Key Questions:

- How were the Boat People from Vietnam treated in Canada?

- Did we learn from history or did we repeat it?

Four decades after the St. Louis event, thousands of refugees, mostly Vietnamese, fleeing the horrors of war in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, asked Canada for asylum.

Here are the facts

Push Factor

Vietnam was one of many places in Asia and Africa fighting for independence after World War II. Like Korea, Vietnam was divided into a communist north and a non-communist south. After decades of French occupation and then American involvement in a decades-long Vietnam War, the victorious north moved to take over the entire country.

Many in South Vietnam, as well as people from neighbouring Laos and Cambodia, fled the country fearing retribution from the North Vietnamese and their allies. Between 1975 and 1976, Canada admitted 5,608 Vietnamese immigrants. In the late 1970s, the communist government stepped up its campaign to punish the southerners through labour camps and other forms of imprisonment. At that point, the fleeing population increased dramatically as thousands of refugees used boats to get away. These vessels were often old and crudely made. Many were ethnic Chinese who were also being forced out of the country.

According to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees, between 200,000 and 400,000 boat people died at sea. Other estimates are that 10 to 70 percent of the 1-2 million Vietnamese died in transit.

Canada was one of many countries asked to help. Many Canadians, some of whom were immigrants and refugees from earlier decades wanted to sponsor refugee families: to help with food, clothing, and shelter until the newcomers could make a go of it on their own.

But many other Canadians opposed helping the refugees. Some feared that Canada could not handle the numbers and made claims that if we took them in we would get hundreds of thousands of people who would be dependent on public money for generations. Some opponents were concerned about a shifting “racial balance” should the refugees be admitted. At this time Canada was going through a bad time economically, and the Trudeau government had just lost the election to a Progressive Conservative government under Joe Clark.

So what was the government to do when any decision would be criticized?

At the time, historians Irving Abella and Harold Troper were working on a history of Canada’s treatment of the Jews during the Nazi period from 1933-45. Feeling empathy with the Vietnamese refugees, based on their research about Jewish refugees who had been denied access to Canada and the United States, they put together a manuscript of their work and mailed it to the office of Ron Atkey, Minister of Employment and Immigration in Ottawa. When the minister read what would eventually be turned into a book called None Is Too Many, he realized the parallels with the refugee crisis in the 1930s and convinced the government to make a decision.

The government decided that the number of boat people should be based on public support. In July 1979, it introduced a matching formula whereby the government sponsored one refugee for each one sponsored privately. The experiment succeeded so that, in addition to the government’s original quota of 8,000, another 42,000 refugees (21,000 privately-sponsored and 21,000 government-sponsored) came over two years. The Canadian Jewish Congress and the Catholic Archdiocese of Toronto were two organizations that sponsored hundreds of families to reach the sponsorship goal.

More refugees from southeast Asia came during the 1980s in smaller numbers. They had to learn English or French and settled in Canada’s larger cities as well as communities where there had never been Vietnamese immigrants.

Considering that they came during a downturn in Canada’s economy, you may wonder how did they do?

KIM PHUC STORY

Here is one story:

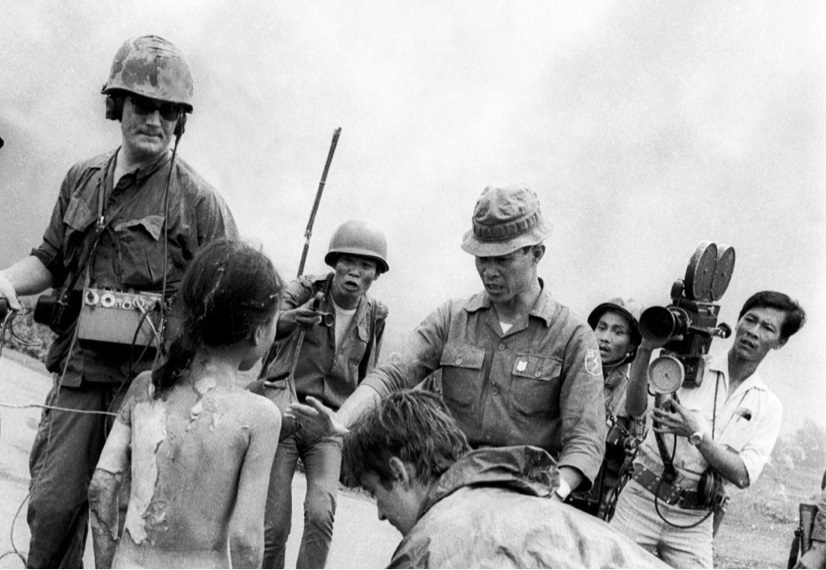

Phan Thị Kim Phúc and her family were residents of the village of Trang Bang, South Vietnam. In June 1972, their village was attacked and captured by the North Vietnamese. Kim Phúc, then 9 years old, joined a group of civilians and South Vietnamese soldiers who were fleeing the country. From the air, the soldiers were mistaken for North Vietnamese. A South Vietnamese Air Force pilot bombed the group and killed two of Kim Phúc’s cousins and two other villagers. She was badly burned and tore off her burning clothes.

Artifact

Artifact

One of the photos (not this one) became world famous as a powerful image of the horrors of war.

Why was that photo not included here?

In an interview many years later, she recalled she was yelling, Nóng quá, nóng quá (“too hot, too hot”) in the picture. New York Times editors were at first hesitant to consider the photo for publication because of the nudity, but eventually approved it.

Kim Phúc and the other injured children were taken to a hospital in Saigon. She was expected to die but more than a year later, after more than a dozen operations, she was able to return home. As she returned to her schooling and later came to study medicine Kim was used as a propaganda tool by the Vietnamese government. She was allowed to go to Cuba, also communist, to continue her studies. She met and married another Vietnamese student.

On their way to Moscow for their honeymoon, the plane refueled in Gander, Newfoundland. They saw their chance, left the plane, and asked for political asylum in Canada, which was granted. The couple now live in Ajax, Ontario, near Toronto, and have two children. In 1996, Phúc met the surgeons who saved her life. The following year, she passed the Canadian Citizenship Test with a perfect score and became a Canadian citizen.

Also, in 1997, she established the first Kim Phúc Foundation in the US, with the aim of providing medical and psychological assistance to child victims of war. Later, other foundations were set up, with the same name, under an umbrella organization, Kim Phúc Foundation International.

ACTION 1

iSearch

Research

1. Can you find other examples of Vietnamese refugees who benefitted from coming to Canada and made contributions to our country?

2. There is more about Kim Phúc, including a documentary film, book, and music. Google “the girl in the picture” and explore.

Every effort has been made to gain permission from copyright holders to reproduce borrowed material. The publishers apologize for any errors and will be pleased to rectify them in subsequent reprints and website programming.

Educator Tools