|

Unit 6: Canada Today and Tomorrow

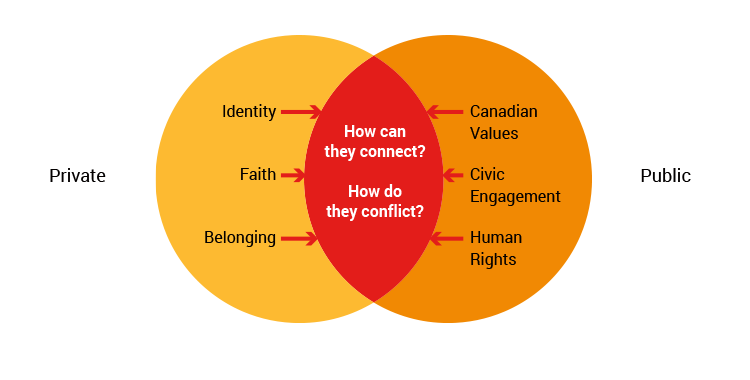

Overview: Canadian Values and Identity

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Educator Tools

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ten things about me | Shared with one person | Shared with two people | Shared with more than two people | |

| 1 | ||||

| 2 | ||||

| 3 | ||||

| 4 | ||||

| 5 | ||||

| 6 | ||||

| 7 | ||||

| 8 | ||||

| 9 | ||||

| 10 |

Discuss

Who are we?

Every personal identity factor can also be considered a group identity.

- Compare charts with your classmates and discuss the identity factors that appear to be shared most often.

Do

Express who you are

- Choose one of the activities below to express your sense of identity and identities.

- Soundtrack of your life

Make an audio track, or compilation, of ten songs that say something important about you. Write a brief description of each song explaining why you chose it. - Aspiration collage

Using images and words from magazines, newspapers and the Internet, make a collage that expresses the kind of person you aspire to be. Write a description of the items you included and what they represent. - Spoken word or rap

Write a spoken word or rap that expresses various aspects of your identity and record it. Include how you would distribute your piece. - Personal logo

Design a logo or symbol that represents who you are. Write a brief description of your logo and how it represents you. Include how you would use it or where you might place your logo.

- Soundtrack of your life

- Post a link to your soundtrack, playlist, spoken word or rap, or a photo of your collage or personal logo on Twitter and/or Instagram, using the hashtag: #VoicesIntoAction.

DO: Take the Video Challenge!

The Our Canada Youth Challenge is for middle and high school students interested in having their writing published or video promoted.

For details, see Action 7.

For more information on the Our Canada Youth Challenge, visit

www.crrf-fcrr.ca/en/our-canada/in-the-classroom

ACTION 2

Belonging

“The whole of the world, the history of the world, is a history of belonging,” says Jean Vanier, a prominent Canadian philosopher, theologian and humanitarian.

Vanier maintains that the desire to belong is a deep psychological drive, that it is part of human nature to need to engage in relationships where we are valued and accepted by others. An individual’s sense of “belonging” refers to how someone locates him/herself within a physical space or within human society, and influences how people relationally connect to one another.

The challenge for all human beings is to balance those identities we share with others, along with those that are important to whom we define ourselves to be as individuals, so that we can establish a common ground to foster harmonious human relations in working towards shared objectives.

Being part of a group awards an individual not only a sense of belonging, but also a sense of security and emotional support. Belonging to a group is also an opportunity for people to expand their horizons and learn from other people, as well as share parts of ourselves and our skills and knowledge with others.

The opposite of belonging is exclusion. It means certain individuals could experience social disadvantage based on the group(s) of which they are perceived to be a part.

For people who relocate to a new place, leaving behind their traditional “group”, the question of belonging is critical to their success and ability to integrate into their new home and society. Canadian society needs to work towards creating an inclusive environment where diversity is recognized, respected and valued, while new Canadians make an effort to enhance their own sense of belonging in Canada by beginning a process of integration, affiliation and connection.

In creating an inclusive environment Canadians, including new Canadians, must commit to learning about the Indigenous peoples of Canada, and the difficulties and current legacy Canadian society must address, to achieve the goal of respecting and valuing diversity. A good place to start is to read the Truth and Reconciliation Commision of Canada: Calls to Action.

– Adapted from Our Canada Handbook

Discuss

Being Part of a Group

UNITY Charity

Engaging and empowering youth to create safer schools and healthier communities.

www.unitycharity.com

Source: Youtube.com

https://youtu.be/NSmF-76JlhE

- What does belonging mean to you?

- What is the connection between having a personal identity, and belonging to a group?

- What groups do you belong to?

- When do your personal identity and need to belong conflict?

- What usually wins in such conflict? Why?

- Belonging can come from taking part in a collaborative project or event:

- What are some of the ways that you can work towards a common cause?

- What events have you participated in that gave you a sense of belonging?

Do

150 Stories

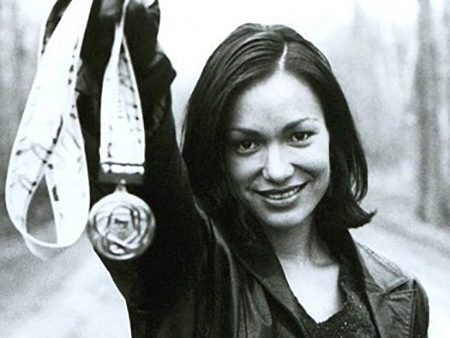

Waneek Horn-Miller: Canada’s Athlete and Ambassador

“The Native concept of power is how much you can empower people around you.”

Source: 22/150 Waneek Horn-Miller

http://bit.ly/1N6k7Vs

150 Stories is a Canadian Race Relations Foundation initiative that is celebrating Canada’s sesquicentennial in 2017 by publishing one story every week for 150 weeks. 150 Stories represents perspectives about Canada and being Canadian, and insights into Canadian history, organizations and initiatives.

Character Study

For this activity, you will read one of the 150 Stories, and create a character study of the person in the story:

- Using a large sheet of paper and a marker, draw an outline of a person and post the outline on the wall.

- With your marker, write the person’s name inside the outline.

- As you read and gain new insights into the storyteller’s identity factors or characteristics, write them down around the character.

- Place those factors you share with the storyteller inside the outline, and those that you don’t share, on the outside of the outline.

- Do you find that you share a lot or a few of the same identity factors?

- Are there any factors you consider to be “Canadian”?

- Write a short response based on your findings.

DO: Take the 150 Stories Challenge!

The Our Canada Youth Challenge is for middle and high school students interested in having their writing published or video promoted.

For details, see Action 7.

For more information on the Our Canada Youth Challenge, visit

www.crrf-fcrr.ca/en/our-canada/in-the-classroom

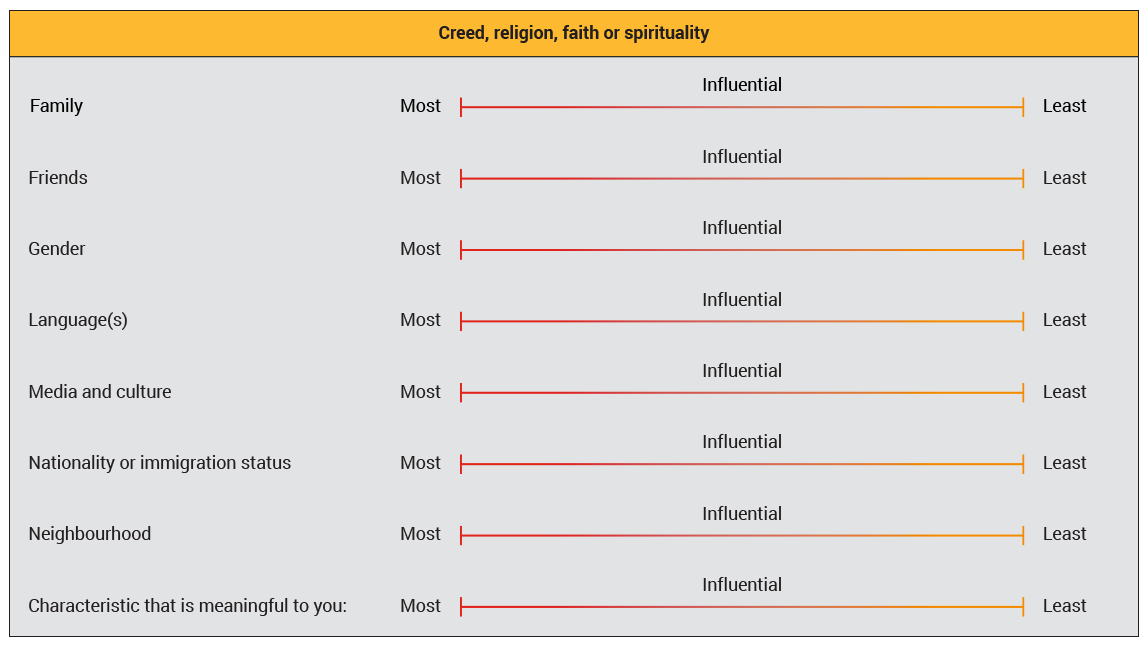

ACTION 3

Creed, Religion, Faith and Spirituality

In learning about the diversity of creed, religion, faith and spirituality in Canada, it is helpful to recognize some common features. There is usually a tradition, or set of stories and practices, transmitted orally or in writing. Some of these traditions, stories and practices can be attributed to a specific founder or set of founders.

Such founding figures are considered great spiritual teachers, prophets or messengers and in some cases, these founding figures themselves come to be seen as divine. Belief in God(s) or the Divine is commonly upheld, although different faiths will refer to different names.

Holy days are associated with history, traditions and accepted ritual practices, as well as a community place of worship, such as a church, gurdwara, mosque, sacred fire, spirit lodge, synagogue or temple.

In many cultures with written texts, the practices and principles, traditions and core values are contained in some authoritative set of sacred writings, such as the Bible or Qur’an for example, either told by and/or written by the founding figure.

Traditional Aboriginal spiritualties have their own distinctive characteristics rooted in the cultures of Indigenous nations and influenced by the unique features and relationships found in individual Indigenous communities. In Indigenous nations, principles and traditions have been passed down for millennia through oral instructions and personal experience, typically through Elders. While there are several common practices among Indigenous groups, there are also specific responsibilities, beliefs and ceremonies associated with each specific band or community.

Many of the teachings, practices and institutions of creeds, religions, faiths and spiritualties remain stable over centuries, but these can also change and evolve over time.

There seems to be one common principle that is shared by all creeds – the “Golden Rule” – which enjoins believers to treat others as they wish to be treated themselves.

– Adapted from Our Canada Handbook

Think

Who said it?

| Match the quotes below to the creed. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Creed | Match | Quote |

|

1. Aboriginal Spirituality |

______ |

A. “Bhikkhus, the middle way, after avoiding the two extremes, gives knowledge and wisdom and leads to calm higher knowledge, enlightenment, nirvana.” |

|

2. The Baha’i Faith |

______ |

B. “Love they neighbour as thyself.” Or “Hear O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is One.” |

|

3. Buddhism |

______ |

C. “…it is not just a faith. It is the union of Reason and Intuition that cannot be defined, but is only to be experienced.” |

|

4. Christianity |

______ |

D. The first responsibility is to the Creator, and to protect the capacity of Mother Earth to host all forms of life, offering thanks to the spirit world, to the spirits of animals, fish and plants, sacrificed for the benefit of people. |

|

5. Hinduism |

______ |

E. “Recite, in the name of your Lord… Recite by the Most Bountiful One your Lord, who by use of the pen taught man that which he did not know.” |

|

6. Islam |

______ |

F. “Though in calm silence I sit I cannot end my search. No mound of earthly pleasures can satisfy my longing for God.” |

|

7. Judaism |

______ |

G. “Blessed and happy is he that ariseth to promote the best interests of the peoples and kindreds of the earth… The earth is but one country, and mankind its citizens.” |

|

8. Sikh Faith |

______ |

H. “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God and the Word was God.” |

Definitions

Definitions

Aboriginal Spirituality: A family of diverse traditions, the practices and beliefs of Aboriginal spirituality respect all reality as sacred. Important to Aboriginal spirituality is respect for all of Creation, both animate and what is perceived as inanimate. The understanding that humans are inextricably part of the web of life – and what we do to that web we do to ourselves – is also fundamental to most Aboriginal ways of knowing.

The Baha’i Faith: This faith is considered by Baha’is to be the fourth of the Abrahamic, monotheistic religions after Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Central teachings are the oneness of God, the oneness of unity of the human family, equality of women and men, harmony of science and religion, importance of eliminating prejudice of all kinds, establishing justice and supporting universal education.

Buddhism: Centred on the “Three Jewels” of Buddhism (Buddha, the ideal model; Dharma, the overall way of life, and Sangha, the community of Buddhist monks and nuns), teachings involve an understanding of the “Four Noble Truths”, that: 1) suffering is universal; 2) craving and desire cause suffering; 3) suffering can be relieved, and 4) following the “noble Eight-fold Path” will relieve suffering. The Eight-fold Path includes right knowledge, right intention, right speech, right conduct, right means of livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness and right concentration.

Christianity: Founded by the followers of Jesus two thousand years ago, Christianity is monotheistic but Trinitarian in its conception of God as the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. Beliefs centre around the virgin birth of Christ, that his death was a sacrifice for the salvation of our souls, and that Christ rose from the dead, appeared to his disciples and ascended to heaven. The sacred book is the Bible. Christianity is the world’s largest and most widely spread religion.

Hinduism: Hinduism is a way of life. Unlike other creeds and religions, it does not claim to have any one Prophet; it does not worship any one God; it does not believe in any one philosophic concept; it does not follow any particular act of religious rites or performances. Hindus believe that there is an underlying principle of divinity or spirit and the entire Universe is ‘superimposed’ on it. Hindus believe in a continuous cycle of reincarnation and rebirth of the soul after death, that the conditions of one’s present life are due to good or bad deeds (Karma) of this life and in past lives. It is the third largest religion after Christianity and Islam.

Islam: Islam is the second largest religion in the world. Muslims believe that Islam is a continuation of Judaism and Christianity, and that the Prophet Muhammad is the Messenger of God. The primary source in Islam is the Qur’an, believed to be the word of Allah and ultimate authority concerning all facets of Muslims’ life. Islam is premised on “Five Pillars”: 1) the profession of recited daily; 2) daily obligatory prayer facing the Qiblah, or Mecca, recited five times daily; 3) “Zakat” or alms giving; 4) fasting between sunrise and sunset during the Muslim month of Ramadan, and 5) pilgrimage to Mecca, known as a “hajj”.

Judaism: The oldest of monotheistic religions, Judaism is based on the Hebrew Bible (known by Christians as the “Old Testament”), which tells the story of God’s purpose for humanity and the Jewish people, revealing the nature of God’s relationship to the people of Israel through God’s Covenant. Jewish laws are of great importance in traditional Judaism and include dietary restrictions for devout Jews and prescriptions concerning prayer and worship as well as rites of passage (such as the coming-of-age ceremony known as the “Bar” or “Bat Mitzvah”).

The Sikh Faith: One of the youngest of the world’s religions, the Sikh faith was founded by Guru Nanak in the late 15th/early 16th century Punjab. It places importance on the search for eternal truth, belief in reincarnation, and four principal ceremonies (naming, initiation, marriage and death), as well as daily observances: morning bath, meditation on the Name of God, and recitation of hymns and prayers three times each day.

– Adapted from Our Canada Handbook

Discuss

Faith in the Classroom

- What creeds, religions, faiths or spiritualties are represented in your class?

- How do your class’s numbers compare to the Canadian population represented by the 2011 Survey results below?

- The Survey link below, also includes a breakdown by province or territory. How do your class’s numbers compare to the population of the province or territory where you live?

Here are the facts

Canadian population by religion, Statistics Canada’s 2011 National Household Survey.

| Total population | 32,852,320 |

| Aboriginal Spirituality | 64,940 |

| Catholic | 12,810,705 |

| Protestant | 2,007,610 |

| Christian Orthodox | 550,690 |

| Christian not included elsewhere | 6,733,740 |

| Muslim | 1,053,945 |

| Jewish | 329,500 |

| Buddhist | 366,830 |

| Hindu | 497,960 |

| Sikh | 454,965 |

| Eastern religions | 32,930 |

| Other religions | 97,900 |

| No religious affiliation | 7,850,605 |

*Based on the population in private households rather than the total population of Canada.

iSearch

Match the Symbols

| Match the symbols to the creed. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Creed | Match | Symbol |

| 1. Aboriginal Spirituality | ______ | A.  |

| 2. The Baha’i Faith | ______ | B.  |

| 3. Buddhism | ______ | C.  |

| 4. Christianity | ______ | D.  |

| 5. Hinduism | ______ | E.  |

| 6. Islam | ______ | F.  |

| 7. Judaism | ______ | G.  |

| 8. Sikh Faith | ______ | H.  |

Discuss

The Faith Project

Films & iPad App

The rituals of seven young Canadians from different faith traditions.

Source: http://thefaithproject.nfb.ca/

The Faith Project is an immersive media experience that intimately observes the rituals of seven young Canadians from different faith traditions.

Each of the project’s subjects allowed the creative team access to their personal practice and expressions of faith. These articulate, busy young Canadians weave faith into their daily lives not as an obligation but as something that is essential to their identity and place in the world.

Similarities and Differences

- What creeds, religions, faiths and spiritualties are present in your local community?

- Which are more important in creating a sense of Canadian identity, our similarities or our differences?

Definitions

Definitions

Aboriginal Peoples: The descendants of the original inhabitants of North America. Term used to collectively describe three groups – recognized in the Constitution Act, 1982: Indians, Inuit, and Métis. These are separate peoples with unique histories, languages, cultural practices, spiritual beliefs, and political goals. The word “Aboriginal” is an umbrella term for all three peoples, and is not interchangeable with “First Nations.” It should also not be used when referring to only one or two of the three recognized groups.

Acceptance: Affirmation and recognition of those whose race, creed, religion, nationality, values, beliefs, etc. are different from one’s own.

Creed: A professed system and confession of faith, including both beliefs and observances or worship. A belief in a God or Gods or a single supreme being or deity is not a requisite.

Ethnicity: The multiplicity of beliefs, behaviours and traditions held in common by a group of people bound by particular linguistic, historical, geographical, religious and/or racial homogeneity. Ethnic diversity is the variation of such groups and the presence of a number of ethnic groups within one society or nation.

First Nation: A term that came into common usage in the 1980s, to replace the term “Indian,” which some people find offensive. It has no legal definition. “First Nation peoples” or “First Nations” refers to the Indian peoples in Canada, both status and non-status, and can also refer to a community of people as a replacement term for “band” (see “Band”). First Nation peoples are one of the distinct cultural groups of Aboriginal peoples in Canada. There are 52 First Nations cultures in Canada, and more than 50 languages. The term “First Nation” is not interchangeable with “Aboriginal,” because it does not include Métis or Inuit.

Indigenous: First used in the 1970s, when Aboriginal peoples worldwide were fighting for representation at the U.N., and now frequently used by academics and in international contexts (e.g., the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples). Understood to mean the communities, peoples, and nations that have a historical continuity with pre-invasion, pre-settler, or pre-colonial societies that developed on their territories, as distinct from the other societies now prevailing on those territories (or parts of them). Can be used more or less interchangeably with “Aboriginal,” except when referring specifically to a Canadian legal context, in which case “Aboriginal” is preferred, as it is the term used in the Constitution.

Race: Refers to a group of people of common ancestry, distinguished from others by physical characteristics such as colour of skin, shape of eyes, hair texture or facial features (this definition refers to the common usage of the term ‘race’ when dealing with human rights matters. It does not reflect the current scientific debate about the validity of phenotypic descriptions of individuals and groups of individuals). The term is also used to designate social categories into which societies divide people according to such characteristics.

ACTION 4

Canadian Values

Who we are, how we were socialized throughout our lives (at home, in school, in the neighbourhood, etc.) and with whom we hang out can shape our beliefs and values.

Values are defined as “one’s principles or standards; one’s judgment of what is valuable or important in life.”

Canada is a democracy, made up of people from all different backgrounds, and therefore Canadian values can be viewed as dynamic, or changing over time, and may be different to different people at different times. Nevertheless, there are some values that can be more clearly noted as “Canadian”, but it would be difficult to show that national values applied to all Canadians all of the time.

According to the Canadian Race Relations Foundation’s Report on Canadian Values, Canadians hold as their most cherished values freedom, equality and loyalty to country. They also value civility, including social etiquette. Canadians are guaranteed equality before and under the law, and equality of opportunity regardless of their origins.

In 1982 the Canadian government enacted the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which includes:

- Freedom of expression

- The right to a democratic government

- The right to live and to seek employment anywhere in Canada

- Legal rights of persons accused of crimes

- Aboriginal peoples’ rights

- The right to equality, including the equality of men and women

- The right to use either of Canada’s official languages

- The right of French and English linguistic minorities to an education in their language

- The protection of Canada’s multicultural heritage

- A desire for peace

The Charter covers the laws and regulations governments can pass and how these are applied. Generally speaking, any person in Canada, whether a Canadian citizen, a permanent resident or a newcomer, has the rights and freedoms contained in the Charter.

There are some exceptions. For example, in section 25 of the Charter Aboriginal rights shall not be abrogated or derogated by the Charter and it gives some rights only to Canadian citizens, such as the right to vote and the right “to enter, remain in and leave Canada”.

– Adapted from Our Canada Handbook

Do

Make a List of Values

What does the term “Canadian values” mean to you?

- Make a list of what you consider to be Canadian values.

- Compare your list with your classmates:

- Which values are the same and which ones are different?

- Why do you think some are different and some are similar?

Discuss

Shared Values

- Do you think Canadian values have changed over time?

- How do your personal beliefs agree with, or conflict with, what you believe are “Canadian values”?

- Where conflicts exist, how do you deal with these challenges?

Do

Rate Canadian Values

Based on the premise that establishing a strong sense of Canadian identity and belonging leads to an inclusive Canada, it has been suggested that one of the most pertinent elements is a shared set of values.

The following values were explored in the Report on Canadian Values.

- Review the list and add any values you feel are missing.

- Rate the values in terms of their importance from 1-10 (1 being most and 10 being least).

- Post your top three values on Twitter and/or Instagram, using the hashtag: #VoicesIntoAction.

| Importance | Value |

|---|---|

| Civility toward others, mutual respect and politeness | |

| Democracy and the rule of law | |

| Equality and equal access to basic needs (e.g. health care and education) | |

| Generosity, compassion and empathy toward others | |

| Humility, modesty about who we are | |

| Loyalty to Canada | |

| Multiculturalism – respect for cultural and religious differences | |

| Official Bilingualism | |

| Patriotism | |

| Respect for human rights and freedoms | |

| OTHER(S) |

Do

Create a Bulletin Board

Over a period of time, watch the newspapers, news magazines and Internet news. Using images and words cut out of these news publications, create a bulletin board display divided into two sections, one for items that you agree do exemplify Canadian values, and those that do not.

- Which section has the most items?

- Post a photo of your bulletin board on Twitter and/or Instagram, using the hashtag: #VoicesIntoAction.

Discuss

Unique Values

Consider whether your parents or teachers share these values and the importance you and your classmates have placed on them.

- Are there any values unique to students? Teachers? Parents?

- Do our values change over our lifetime? If so, how, why and if not, why not?

Do

My Values

Learn about your classmates, their values and the values you share. While retaining what is unique about you, it is helpful to emphasize common and broader shared values and principles, rather than narrower dividing ones.

- In column 1 list your ten top values.

- Compare your values with others.

- If you share a value with one other person, put his/her name in column 2.

- If you share a value with two other people, add the second person’s name to column 3.

- If you share a value with more than two people, add their name(s) to column 4.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| My top ten values | Shared with one person | Shared with two people | Shared with more than two people | |

| 1 | ||||

| 2 | ||||

| 3 | ||||

| 4 | ||||

| 5 | ||||

| 6 | ||||

| 7 | ||||

| 8 | ||||

| 9 | ||||

| 10 |

ACTION 5

Civic Engagement

In Canada we are not just a collection of isolated communities; we also have a responsibility to the common good.

Understandably, the ability to influence societal change is a significant component of living in a democracy. But there is more to democracy than a jaunt to the ballot box every four years.

Civic engagement is about the right of the citizen to influence the public good, determine how best to seek that good and contribute to reforming the institutions that do not serve the public good as well as they should.

By being an engaged citizen we help our society grow. In the end, when active citizens take a leadership role and contribute their time, energy and good will, the rewards are many.

Participation can include efforts to directly address an issue, concern or need, and to collaborate with others in your community to realize a goal, problem-solve or interact with institutions. Action begins when individuals feel the sense of personal responsibility to uphold their obligations as part of any community, and strive to make a contribution in a meaningful way. We learn from acting together. By collaborating, citizens build public institutions such as schools and hospitals, and intangible ones like traditions and norms.

– Adapted from Our Canada Handbook

Discuss

Contributing to Your Community

- What are you doing for your community service hours?

- How is this contributing to your community?

- Is it contributing to your sense of community engagement? If not, what would make the experience more relevant?

Think

What can you do? Become an active participant!

- What is the path to civic engagement and how can it be fostered it in a meaningful way?

- How can you impact public issues by devoting time and energy with your family, friends, community, or on your own, towards initiatives of public interest?

- What can you do to foster a greater sense of civic engagement in your community?

Canadian Roots Exchange

Building bridges between Indigenous and non-Indigenous youth by facilitating dialogue and strengthening relationships through leadership programs.

www.canadianroots.ca

Source: YouTube

https://youtu.be/kGDJ5nuuKkI

Research some organizations and causes that interest you:

- Join: As an active member of a group or an association that reflects your values, ethnocultural or linguistic background, and/or your skills, expertise, training, education or interests.

- Volunteer: At a food bank, health care or community centre, place of worship or other non-profit organization or charity.

- Fundraise: Walking, running, organizing, and supporting causes that are important to you.

Do

Create a Bulletin Board

- As a class, use newspapers, magazines or download images from the Internet to create a bulletin board representing all the civic engagement activities undertaken by the class as a whole.

- Classify them as Join, Volunteer, Fundraise and any others you have identified.

- Post a photo of your bulletin board on Twitter and/or Instagram, using the hashtag: #VoicesIntoAction.

Consider:

- What are the most popular forms of engagement?

- How do these activities reflect your values as a group?

- What is the collective impact of the class, and on the class?

- Is there a way your class can make a difference by working on a project that reflects your shared values?

Think

Voting

When it comes to civic engagement on an electoral platform, the first thing that comes to mind for many of us is voting.

Student Vote is a parallel election for students under the voting age, coinciding with federal, provincial, territorial and municipal elections. The purpose is to provide young Canadians with an opportunity to experience the voting process firsthand and build the habits of informed and engaged citizenship. Students take on the role of election officials and cast ballots for the official election candidates.

- Do you think that it is important for students under the voting age to engage in the electoral process? If so, why? If not, why not?

- If your class registers for Student Vote, post your campaign on Twitter and/or Instagram, using the hashtag: #VoicesIntoAction.

Student Vote

Your school can register and hold its own Student Vote Day. The program is completely free. http://www.studentvote.ca

Source: CIVIX Canada www.civix.ca

Since 2003, 27 Student Vote programs have been conducted across Canada at the federal, provincial, territorial and municipal levels of government. In the most recent federal election, 922,000 students cast ballots from 6,760 schools.

Discuss

Beyond the Ballot Box

Democratic participation can, however, be extended past the ballot box. Do you think it is important to get involved in any of the following activities?

- Volunteering to work for a candidate, political party or a political organization?

- Developing a political voice at the municipal, provincial/territorial or national level?

- Encouraging friends and family to get involved as well?

Do

How can you be heard? Identify, discuss, collaborate, and connect.

- Identify an issue that is vital to you and your classmates.

- What opinions do your classmates have on the issue?

- By sharing your ideas and experiences, does it shed light on a particular situation for you?

- Collaborate with your classmates to create insights and a list of possible solutions to the issue. You might decide to break into smaller groups tackling different issues.

- Set up three questions and interview one or more people about the issue. You could do this within your school or broader community.

- Bring all the interviews together and share them with your group*.

- Did you learn something new, or were the responses mostly the same?

- Review your list of solutions: have the interviews introduced new or different solutions?

*Your class might consider sharing your interviews through a blog, or recording your interviews and turning them into a podcast. If you do, then post a link to your blog or podcast on Twitter and/or Instagram, using the hashtag: #VoicesIntoAction.

Interview Guidelines

- Attempt to listen to people with differing points of view.

- Make sure your questions are clear and concise – have translations and definitions of terminology where necessary.

- Sticky issues are part of the process, so do not shy away from them.

- Go in search of people from different socio-economic, ethnic and cultural backgrounds, as well as people of different genders and ages, and include them in the discussion.

- Share the idea(s) in clear, concise language because you would like many people to understand and be part of the solution.

ACTION 6

Pluralism in Canada: Multiculturalism & Interculturalism

Canada, a land rich with culture, language and history, was first inhabited by Aboriginal peoples – comprised of a multitude of distinct Indigenous nations which today are known under three general groupings: First Nations, Inuit and Métis. First Nations and Inuit occupied the lands of North America long before the arrival of Europeans. At the beginning of the 15th century, French and English explorations brought settlements to eastern Canada, developing trade and establishing colonies. The Métis as a distinct group arose after the arrival of the Europeans. They are a result of intermarriage between Europeans and the Indigenous peoples.

With the exception of Indigenous peoples, everyone in Canada is an immigrant or a descendent of one.

Throughout its early years, Canada favoured immigration from British, Anglo-American and western European sources. In the first half of the 20th century, European immigrants came to Canada from such countries as Poland, Italy, Germany, Ukraine, Ireland and Portugal. During the mid-half of the century and on, Canada attracted immigrants from the Caribbean, Middle East, South America, Africa and Asia.

In the early 1960s, many Canadians grew increasingly dissatisfied with the predominantly Anglo-centric character of their political, economic and social institutions. Although much of the discontent emanated from Québec, the Indigenous peoples and various ethnic groups were also requesting changes.

In response, the Federal government, in 1963, appointed the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism, whose mandate was to recommend steps to develop the Canadian Federation between the English and the French. The Commission’s report reaffirmed Canada’s bilingual and bicultural reality. One of the most important recommendations was to make Canada an officially bilingual nation, achieved through the introduction of the Official Languages Act, and the encouragement of students across the country to learn both official languages.

In 1971, the Federal government, under the leadership of then Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau, took a direction different than the Commission’s recommendations and pursued a policy of “multiculturalism within a bilingual framework”. Hence, Canada be- came the first country in the world to adopt a national multiculturalism policy.

The policy was an attempt to reconcile two competing visions of Canada: the dualistic view, that, in addition to the Indigenous Peoples, Canada is comprised of two principal founding groups; and the pluralistic view, which sees Canada as comprised of a wide variety of cultural groups. The policy encouraged all Canadians to accept cultural pluralism and to participate fully and equally in Canadian society. Multiculturalism remains an integral part of our national identity and, as such, Canada has been unique among western democracies in its commitment to this ideal.

By 1981, as Canada’s racial diversity was beginning to grow, more attention was being devoted to racial discrimination, and race relations. With the experience of Indigenous peoples of Canada rising up to oppose the 1969 White Paper that proposed to eliminate Indigenous rights and with the support of some Canadian church groups, Aboriginal or Indigenous rights were affirmed in the Constitution Act of 1982 as they had been in the Royal Proclamation of 1763. In 1982, with the repatriation of the Canadian Constitution, multicultural policies were firmly entrenched in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms guaranteeing, among other things, equal protection and benefit of the law, and freedom from discrimination on the basis of, for example, gender, creed, religion, racial and ethnic origin.

As such, multiculturalism was recognized in Section 27 of the Canadian Charter in 1982. An objective of Canada’s multiculturalism policy was to foster a more just society, with early multicultural programs emphasizing cultural pluralism. Over time, the shift in focus to equity and anti-discrimination measures widened the meaning of multiculturalism to include issues relating to anti-racism. These programs, strengthened by policy initiatives, have been effective in bringing about advancements in opportunities for minority groups.

In 1988, Bill C-93, the Multiculturalism Act, was passed and became the first formal legislative vehicle for Canada’s multicultural policy. The Multiculturalism Act affirms the policy of the government to ensure that every Canadian receives equal treatment by the government, which respects and celebrates diversity.

The Act went beyond simply guaranteeing equal opportunity for all Canadians, regardless of origin. It emphasized the right of Canada’s ethnic, racial and religious minorities to preserve and share their unique cultural heritage, and underlined the need to address race relations and eliminate systemic inequalities.

Each of Canada’s provinces has a recognized multicultural policy in place. Saskatchewan was the first Canadian province to adopt legislation on multiculturalism, which was called The Saskatchewan Multiculturalism Act of 1974, which has since been replaced by a new, revised Multiculturalism Act (1997). Ontario followed in 1977 by putting in place a policy that promoted cultural activity, which became an Act in 1990, and the final province being Newfoundland and Labrador in 2008.

Quebec and “Interculturalism”

Quebec differs from the other nine provinces in that its policy focuses on “interculturalism” rather than multiculturalism, wherein diversity is strongly encouraged, but subsumed under the notion that it is within the framework that establishes French as the public language.

Quebec’s policy of interculturalism, which was developed in reaction to the federal multiculturalism policy, recognizes the reality of the province’s identity as a distinct Francophone community, where the French language and culture hold paramount importance. For example, immigrant children must attend French language schools and most signage must be in French.

In 1990, Quebec released Let’s Build Quebec Together: A Policy Statement on Integration and Immigration, which reinforced the notions of Quebec as a French-speaking society; Quebec as a democratic society wherein each person is expected to contribute to public life, and Quebec as a pluralistic society which respects the diversity of cultures within a democratic framework. In 2005, Quebec developed the Ministry of Immigration and Cultural Communities with the primary function being to foster closer cultural relations among the people of Quebec, and to support cultural communities in their quest to participate fully in Quebec society.

– Adapted from Our Canada Handbook

Do

Newspaper Scavenger Hunt

In small groups of 3 or 4, search through a selection of newspapers and news magazines to find items on the list below. You have 15 minutes (or more, to be determined by the class/teacher) to find as many as possible.

Hunt Ideas

- A picture of something you consider “Canadian”

- An article about some aspect of Canadian culture

- An article or photo showing people in Canada taking part in cultural traditions from another country

- A word in the paper that is in a language other than English or French

- A story or picture from the sports section representing a game more common outside of Canada

- An example of someone showing their identity as a person

- An ad for a job requiring more than one language

- An ad appealing to your identity, persuading you to buy something

- An editorial or article talking about human rights

- A story about events in a foreign country that could affect Canadians

- An article dealing with an important local issue

- A picture or story about “ethnic” foods or entertainment

- An article about a clash of rights or values

- An article that discusses issues important to Aboriginal Peoples in Canada

- A photo of two or more people from different backgrounds working together

Share and present your findings to the class:

- Which items were easy to find?

- Why do you think some items were easier to find than others? And what are the implications of this (i.e., what types of things tend to be omitted from some or all of the newspapers and why?)?

- How can you justify the choices you made to fit each item on the list?

Do

Demonstrate Diversity

- Create a visual piece that demonstrates diversity in your classroom or community by choosing one of the following activities:

- Make a photo essay with accompanying commentary

- Make a short animated video piece. This could be either drawn, or computer generated animation, or a stop motion animation.

- Post your photo essay or animated video on Twitter and/or Instagram, using the hashtag: #VoicesIntoAction.

Discuss

What it Means to be a Multicultural Society

In order for Canada to be a truly multicultural society, it is necessary to incorporate ideas and knowledge from all cultures in how we organize our work and living space, our education systems, our popular culture and mass media and all other aspects of society. Canada as a society needs to fully embrace equality and justice for all of its residents, no matter their background, gender, ethnicity, faith, tradition or skin colour.

- What knowledge or practices from non-Canadian cultures do you think should be incorporated into Canadian society?

- How would you like to see policies around multiculturalism or interculturalism progress in Canada?

Do

The Evolution of Multiculturalism

Augie Fleras and Jean Lock Kunz conceived this table in 2001 to represent the ways that multiculturalism has changed since the Multiculturalism Act was introduced in 1970.

| Ethnicity Multiculturalism (1970s) | Equity Multiculturalism (1980s) | Civic Multiculturalism (1990s) | Integrative Multiculturalism (2000s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focus | Celebrating differences | Managing diversity | Constructive engagement | Inclusive citizenship |

| Reference Point | Culture | Structure | Society building | Canadian identity |

| Mandate | Ethnicity | Race relations | Citizenship | Integration |

| Magnitude | Individual adjustment | Accommodation | Participation | Rights and Responsibilities |

| Problem Source | Prejudice | Systemic discrimination | Exclusion | Unequal access, “clash” of cultures |

| Solution | Cultural sensitivity | Employment equity | Inclusiveness | Dialogue / Mutual Understanding |

| Key Metaphor | “Mosaic” | “Level playing field” | “Belonging” | “Harmony/Jazz” |

Reference: Augie Fleras and Jean Lock Kunz. 2001. Media and Minorities, Representing Diversity in Multicultural Canada. Thompson Educational Publishing.

As a class or in groups:

- Review the “Evolution of Multiculturalism” table (above) created by Fleras and Kunz, 2001.

- Create a “Next” column and complete it with the way you would characterize the current/next stage of multiculturalism in Canada.

- Compare your ideas with the updated version of the table put forward by author Andrew Griffith, formerly Director General, Citizenship and Multiculturalism Branch, Department of Citizenship and Immigration (Slide 7).

- This work is from his new book “Multiculturalism In Canada: Evidence and Anecdote”. Andrew also regularly writes for his blog, “Multicultural Meanderings”.

- With the new government’s focus on diversity and inclusion, should Andrew’s table be updated even further, and if yes, how?

Andrew Griffith

Andrew Griffith’s updated version of the table The Evolution of Multiculturalism is Slide 7.

Source: CRRF Webinar, Multiculturalism and the Power of Words, October 2015

http://bit.ly/1OMjC5q

ACTION 7

Our Canada 2016 Youth Challenge

The Youth Challenge was held in 2016 for Canada’s 150th birthday. Middle and high school students submitted writing or videos: The Youth Challenge

150 Stories:

Go to the Canadian Race Relations Foundation site www.crrf-fcrr.ca and search “150 stories”. You will be able to choose from 150 different stories by Canadians who have made a difference. Here are examples of 5 of the 150 stories:

150 Stories Kathleen Livingstone

150 Stories Mimi Freedman

150 Stories Mohinder Grenwal

150 Stories Amira Elghawaby

150 Stories Moses A. Mawa

Diviya Leonard: A Canadian Girl Making a Difference

“My name is Diviya Leonard and I am proud to call myself Canadian. I am now 14 years old, but I started getting involved with human rights issues when I was 11.”

Source: 41/150: Diviya Leonard

150 Stories Diviya Leonard

Daniel Roher: Building Bridges Among Canada’s Treaty People

“It is through documentary that I try to provide new perspectives and contemporary understandings to help build the bridge among all of Canada’s treaty people.”

Source: 28/150: Daniel Roher

http://bit.ly/1OeBilr

“I am Canadian” 2014 Winning Youth Video

Produced by Harley Manitowabi, Hillcrest High School, Ottawa, Ontario

Answers to Action 3 activities

Think, “Who said it?”

Answers: 1/d; 2/g; 3/a; 4/h; 5/c; 6/e; 7/b; 8/f.

Match the symbols

Answers: 1/c; 2/e; 3/g; 4/h; 5/d; 6/b; 7/a; 8/f

ACTION 3, The Faith Project

The Faith Project can be found on CAMPUS, National Film Board’s online education portal. The unit explores themes such as spirituality, beliefs, knowledge, the secular world, practicing faith in Canada and working together.

Every effort has been made to gain permission from copyright holders to reproduce borrowed material. The publishers apologize for any errors and will be pleased to rectify them in subsequent reprints and website programming.

Educator Tools