|

Unit 3: Prejudice and Discrimination

Chapter 6: WWII Japanese Internment Camps

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Educator Tools

|

| Year | Events in History |

|---|---|

| 1877 |

|

| 1885 |

|

| 1899-1902 |

|

| 1907 |

|

| 1914 |

|

| 1916-1922 |

|

| 1931 |

|

| 1937 |

|

| 27 September, 1940 |

|

| 1941 |

|

| 1942 |

|

| 19 January, 1943 |

|

| 2 May, 1947 |

|

| 31 March, 1949 |

|

ACTION 1

Two terms— “internment camps” and “concentration camps” are used to describe camps in which civilians are interned. Sometimes the terms are used interchangeably. Should they be?

iSearch

Research the use of these two terms as they have been used throughout history and conduct the following test using the Venn Test.

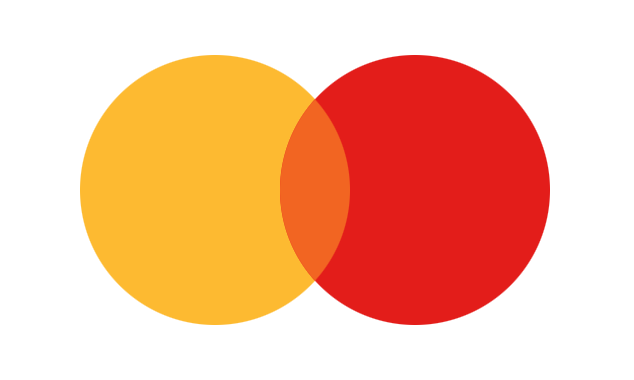

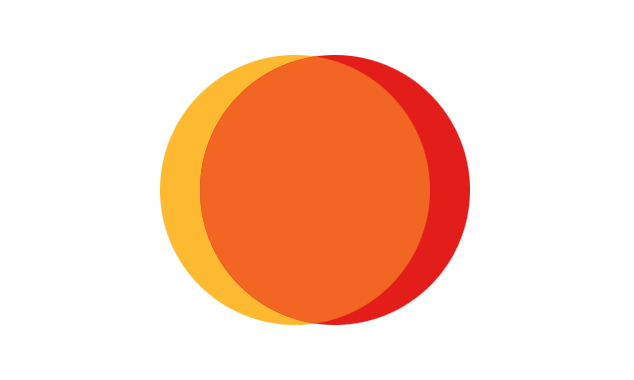

Venn diagrams help us to compare–a key ingredient for improving your understanding of concepts. Here is a test to enhance comparison and contrast. We can compare two ideas:

› “prejudice” and “discrimination”

Or the experiences of two groups of immigrants:

› Chinese and Japanese Canadians from early settlement to 1949

Or experiences in Canada and the United States:

› the treatment of people with Japanese ancestry

A. Do the people, events, or ideas being compared have nothing in common?

B. Are any similarities overshadowed by their differences?

C. Are their similarities so strong that their differences do not matter that much?

D. Are they synonymous: do they constitute the same thing, although they go by different names?

E. Is one idea a part of the other idea?

This test can be used in all subject areas when comparing, for example:

- Two (or more) historians’ accounts of an event, idea, or person (artifacts).

- Editorials from two newspapers on a current issue related to prejudice, discrimination, human rights, or any other topic found in Voices into Action.

The Venn Test is more open-ended than a simple Venn diagram and promotes deeper analysis of patterns and relationships.

Discuss

Using the Venn Test, discuss and debate these issues in pairs or larger groups. Some comparative relationships may be a matter of judgment in which there may more than one correct answer.

ACTION 2

Do

From the timeline and classroom work, including studying other Voices into Action chapters and units, you know that there was unfair prejudice against many Canadians throughout our history involving many acts of discrimination by individuals, organizations, and even the government. Examine another group that suffered prejudice and discrimination throughout our history (and perhaps found within Voices into Action) and compare with the Japanese Canadian experience using the Venn Test.

Artifacts 1

Artifacts 1

The following documents, both primary and secondary sources, relate to the decision to remove Japanese Canadians from the west coast.

Document 1: › Parts of a resolution passed by the British Columbia Legislature in 1924

Whereas statistics show that there is a large increase in the number of Orientals (Chinese and Japanese) in British Columbia, multiplying each year to an alarming extent:

And whereas the Orientals have invaded many fields of industrial and commercial activities to the serious detriment of our white citizens:

And whereas many of our white merchants are being forced out of business by such commercial and industrial invasion:

Therefore be it resolved that the House go on record as being utterly opposed to the further immigration of Orientals . . .

Ken Adachi, The Enemy That Never Was (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1991), 141.

Document 2: › Statement about Japanese Canadians by British Columbia M.P. Thomas Reid, in a speech in January 1942

Take them back to Japan. They do not belong here . . . They cannot be assimilated as Canadians for no matter how long the Japanese remain in Canada they will always be Japanese.

Roy Miki and Cassandra Kobayashi, Justice in Our Time: The Japanese Canadian Redress Settlement (Vancouver: Talon Books, 1991), 24.

Document 3: ›

On December 7, 1941 Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, the American naval base in Hawaii. This attack brought the war close to North America and created near panic in British Columbia and on the California coast.

The first victims of this growing fear were the Japanese Canadians. About 23,000 of them, not all Canadian born, but almost all citizens, lived in British Columbia. Racism in Canada had existed for a long time, but the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor had raised it to a fever pitch. The federal government in Ottawa was repeatedly told by its officials, the RCMP and by military officers that the Japanese Canadians posed no threat. But the political pressure grew, especially from British Columbia’s representatives in federal cabinet. The government felt obliged to act. The Japanese Canadians were rounded up, deprived of their jobs and property and sent to the interior of BC or to other parts of the country. It was the most shocking violation of basic human rights in Canada during the war.

J. L. Granatstein et al, Twentieth Century Canada, 2nd ed. (Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1986).

Document 4: ›

There were many reports – both real and imagined — of enemy submarine activity off the coast of California in late December 1941. A few American freighters were shelled and one sunk. Although there were no further attacks after December, many coastal residents felt they were under threat from a whole fleet of enemy submarines.

The same panic was evident on the west coast of British Columbia in December 1941. One rumour was that Japan’s main fleet was exactly 154 miles west of San Francisco and heading northeast towards B.C.

The closest thing to an attack on British Columbia’s coast however was the shelling by a Japanese submarine of a radio station and lighthouse on Estaven Point on Vancouver Island in June 1942. The shelling caused virtually no damage. There was no invasion of Canadian soil, no landings from the sea or aircraft bombings. There was no evidence that the Japanese ever seriously considered such steps.

Ken Adachi, The Enemy That Never Was (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1991), 206-208.

Document 5: ›

It would be possible to make the whole of British Columbia a battleground, and even to bomb the prairie cities such as Edmonton and Calgary. We should be protected from treachery, from a stab in the back . . . There has been treachery elsewhere from Japanese in this war, and we have no reason to believe that there will be none in British Columbia . . . the only complete protection we can have from this danger is to remove the Japanese population from the province.

British Columbia M.P. Howard Green in a House of Commons speech, January 29, 1942.

Document 6: ›

For six weeks, from the middle of January 1942 to the announcement of mass evacuation, many community groups in B.C. feared that the Japanese Canadians would betray Canada. Municipal councils, most notably those of Vancouver and Victoria, urged Ottawa to remove all Japanese. The Citizens’ Defense Committee made up of 20 prominent B.C. citizens supported the mass evacuation of the Japanese Canadians. This committee caused a “deep impression” in Ottawa.

“It is a fact that no person of Japanese race born in Canada has been charged with any form of sabotage or disloyalty during the war years,” said Prime Minister Mackenzie King in 1944. He also could have added that no Japanese Canadian, wherever born, had ever been found guilty of such crimes.

Ken Adachi, The Enemy That Never Was (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1991), 206 and 276.

Document 7: ›

An important factor guiding federal policy at this time was the fall of Hong Kong in late December 1941, and the capture of Canadian soldiers there. As well, reports of Japanese treatment of prisoners in Hong Kong greatly increased the hostility towards the Japanese residents on the west coast.

On February 19, 1942, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King recorded in his diary that he was fearful of riots on the west coast. He thought those riots might be caused by reports of mistreatment of Canadian prisoners. King wrote, “Once that {rioting} occurs there will be repercussions in the far east against our own prisoners.” It was partly in fear of such reprisals that King decided that all Japanese must be evacuated.

The mass removal of the Japanese Canadians also would remove a widespread fear among the white population which might lead to riots.

Ken Adachi, The Enemy That Never Was, Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1991, p. 211.

Document 8: ›

During the sixty-five years since the first settler from Japan came to Canada in 1877, legal restrictions in British Columbia denied them the right to vote or be elected to public office. In addition, they were prevented from entering professions such as law, pharmacy, teaching and accounting.

The uprooting of Japanese Canadians in 1942 was not an isolated act of racism, but the end result of discrimination which had build up from the first days of their settlement. Indeed, for many decades, Japanese and Chinese immigrants had been harassed by racists. Older Japanese Canadians remembered well the Vancouver Riot of 1907. A crowd at an anti-Asian rally suddenly turned into a mob, stormed through Chinatown, breaking store windows and were finally beaten back by a group of Japanese Canadians.

Roy Miki and Cassandra Kobayashi, Justice in Our Time: The Japanese Canadian Redress Settlement (Vancouver: Talon Books, 1991), 17-18.

Document 9: ›

In 1942 a special committee in B.C. reported that unless anti-Japanese sentiments were reduced, there would be riots. Such an incident had already occurred in the Japanese Canadian district on Halloween night in 1939 when a mob of 300 white youths smashed plate glass windows and looted stores.

Ken Adachi, The Enemy That Never Was (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1991), 191.

ACTION 3

Do

The Spectrum Line

This organizational structure helps those who are visual learners demonstrate what they know by placing views along a spectrum. Apply it to your learning by discussing a question that can have many possible answers.

- In pairs, use a spectrum worksheet in which you examine a number of significant events related to a question in a social studies area. Number each event.

- The line or scale at the top of the page represents a wide spectrum of views about the question or issue. Opposing criteria are placed at each end of the spectrum line. Work in pairs to reach consensus as to where each event belongs, according to the criteria. If you are looking at the reasons Japanese Canadians were removed from the west coast during World War II, you might locate the historical interpretations offered in the previous 9 documents along the spectrum, based on the identified or implied cause for removal as follows:

- With your partner, position the number of the document on the spectrum line according to its relevance to the issue or question being discussed. For this particular example, you might expect document 2 to be near the “racial fears” spectrum line.

- Write a sentence beside or after each document justifying its position on the line based on your summarized and paraphrased interpretation of the source.

- Team up with another pair to exchange views and attempt to reach a consensus by merging both teams’ spectrum lines.

Another kind of spectrum line is a scaled spectrum that can be used throughout your research of the topics within Voices into Action. When comparisons are required, you may wish to include a Scaled Spectrum (rather than one with just two opposing criteria) with criteria being identified as:

Spectrum Construction – find statements, events, ideas, quotes, etc. to fall on each end and in the middle of the spectrum.

The range of perspectives along the spectrum line can include criteria such as:

- unimportant – very important

- good example – poor example

- good leadership – poor leadership

- strongest influence – weakest influence

Discuss

Artifacts 2

Artifacts 2

The following diary entries and memoirs capture some of the experiences of the internment detainees: http://www.lib.washington.edu/specialcollections/collections/exhibits/harmony/canada/excerpts/oiwa.

First independently, then in pairs, then in groups of pairs, share your reactions (feelings) as you read the entries. Some questions you can ask yourself are:

- What emotions come to you when you read each entry?

- Which adjectives come to mind as you read?

- Can you identify or relate with an experience or a character from a reading? What in particular do you feel/see? How does this connection influence your understanding of the character or event?

A. From the foreword, by Joy Kogawa (author of Obasan):

I devoured these stories in one hungry afternoon of reading. Some of it was painfully familiar. Some of the flavouring tasted strange and felt unsettling. Here were some Issei, professing in their diaries, an identity with a country that was the enemy country of my youth. As a passionately Canadian Nisei, I never did want to believe that Japanese Canadians were anything but totally Canadian in their identity. This was unreasonable. How could I expect people to feel no connection to the land of their birth? As I read, I ranged through discomfort, old sadness, nostalgia, admiration, tenderness, pride, and anger as I was taken back to look again with the help of these additional perspectives, into the secrets and intimacies of my childhood.

B. From the diaries of Koichiro Miyazaki

April 15, 1942

Rain. I haven’t seen rain for a long time. As I look into the birch forest it is shrouded with a gentle spring rain. It is all very dream-like. My diaries, which were confiscated, were returned cut up and censored. It is just an internee’s diary. Do they have the right to do such things? At least they should give some reasons. They can confiscate my diaries but the facts of my life will not disappear… (Oiwa, 52)July 19, 1942

This is the last day of our life at Petawawa internment camp. I remember the day we arrived here when the camp was still surrounded by the harsh, bleak winter. The lake was frozen white. The biting wind was blowing. The ground was hard and icy. The birch forest gave a bleak impression of white skeletons and made us shiver. The whiteness of the landscape is still clearly imprinted in the back of my mind. It so happens that we are leaving here in the middle of summer. Tomorrow morning we are leaving this place for good. The camp is now surrounded by lush green … Many people have cleared the barren land and sowed various vegetables and flowers which our eyes and stomachs have begun to enjoy. Well, I’d better stop being sentimental. Tomorrow a new struggle begins in a new camp … (Oiwa, 61)

C. From the letters of Kensuke Kitagawa (written while interned at Angler Prison Camp):

May 28, 1943 (from a letter to his wife)

I still look at the wisteria branch that you sent me which is on the wall. As I slept in the lower bunk, a haiku came to me:

Wisteria flowers:

But double-decker bed

Is in my wayI wonder how you interpret this poem. Guess where my mind is? (Oiwa, 112)

D. From the diary of Kaoru Ikeda:

… We have seen Canada’s true nature through our recent experiences. What is democracy? Who can talk about it? Who has the right to accuse Japan of invading other countries? Isn’t Britain the champion invader? The last several centuries of British history is full of invasion after invasion. Since they can be neither Japanese nor Canadian, I wonder what the future of the Nisei youth will be? Deprived of civil rights these young people are in a sad situation. I just hope that their efforts will lead to a positive solution. (Oiwa, 146)

E. A tanka poem, written while at Slocan:

I thought

It would only be temporary

In this Mountain country

Accumulate another year

As snow deepens

(Oiwa, 119)

F. In the words of Genshichi Takahashi:

The government promised us that until the end of the war the Custodians would take care of our properties. We trusted the words of the government and left all our belongings behind. These were all very important things to us. They then confiscated and sold for next-to-nothing, our farmland, fishing boats, and cars, by means of the unjust law called the War Measures Act. From the beginning the government intended to deceive us. (Oiwa, 192)

ACTION 4

Do

Writing is one way to express the emotion of a situation. Haiku is a Japanese poetic style that uses sensory language to capture a feeling or image. They are often inspired by an element of nature. The traditional format is three-lines with 17 syllables arranged in a 5–7–5 pattern.

Here is an example that may depict what the Japanese went through:

Discrimination

Prejudice is a dark cloud

Bad for all of us.

Write a Haiku to represent the feelings of a child in an internment camp.

Artifacts 3

Artifacts 3

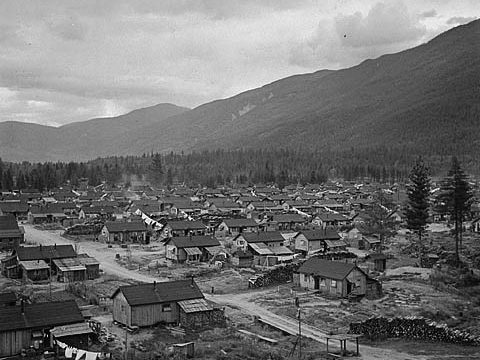

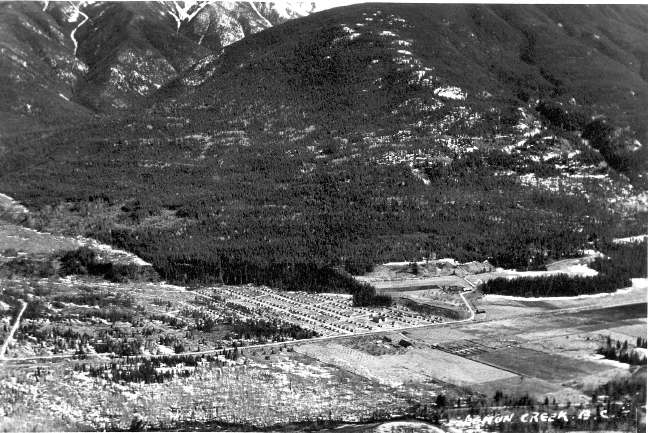

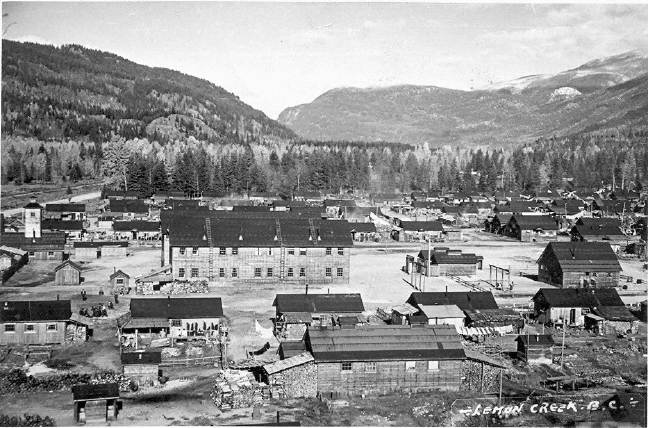

The following are photos from the internment period:

The Lemon Creek Internment Camp, 1944-1945, constructed specifically to intern Japanese Canadian families.

Source:http://www.michaelkluckner.com/bciw4slocan.html

Photos courtesy of Diana Domai.

The Lemon Creek Internment Camp, 1944-1945, constructed specifically to intern Japanese Canadian families. The school in the centre held classes for kindergarten to grade 12.

Source:http://www.michaelkluckner.com/bciw4slocan.html

Photos courtesy of Diana Domai.

ACTION 5

Do

http://www.sedai.ca/archive/photos/collections/internment-camps/

This website has many photos from the internment period. As part of the Japanese Canadian Legacy Project, SEDAI is dedicated to collecting and preserving the stories of earlier generations of Canadians of Japanese ancestry for all future generations to witness.

First on your own, then in pairs, examine the photos above and those on the website. Pick out the photos that have the most emotional impact to you and explain why you feel this way.

ACTION 6

Discuss

“Minoru”, a film by Michael Fukishima portrays the story of his father’s family’s internment during the war.

https://www.nfb.ca/film/minoru-memory-of-exile

After viewing, compare your feelings about the film with other sources about the time, such as photos, memoirs, daily entries, textbook accounts and more.

Discuss:

- How historical context enriches the study of literature and media portrayals

- How literature and media can enhance our understanding of an event in history

ACTION 7

Discuss

On September 22, 1988, the Japanese Canadian Redress Agreement was signed. In the House of Commons, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney acknowledged the government’s wrongful actions, pledged to ensure that the events would never recur and recognized the loyalty of the Japanese Canadians to Canada. As a symbolic redress for those injustices the government offered individual and community compensation to the Japanese Canadians. To the Canadian people, and on behalf of Japanese Canadians, the federal government also promised, under the terms of the agreement, to create a Canadian Race Relations Foundation, which would “foster racial harmony and cross-cultural understanding and help to eliminate racism.” The federal government proclaimed the Canadian Race Relations Foundation Act into law on October 28, 1996. The Foundation officially opened its doors in November 1997. http://www.crr.ca

Prime Minister Brian Mulroney’s remarks to the House of Commons, Sept. 22, 1988

I know that I speak for Members on all sides of the House today in offering to Japanese Canadians the formal and sincere apology of this Parliament for those past injustices against them, against their families, and against their heritage, and our solemn commitment and undertaking to Canadians of every origin that such violations will never again in this country be countenanced or repeated.

CBC News story about the event (4 ½ minutes)

The Redress Agreement of 1988

Front, L-R: Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and Art Miki, President of the National Association of Japanese Canadians signing the Redress Agreement on September 22, 1988. Back, L-R: Don Rosenbloom, Roger Obata, Lucien Bouchard, Audrey Kobayashi, Gerry Weiner, Maryka Omatsu, Roy Miki, Cassandra Kobayashi.

As a class, respond to questions such as:

- What criteria should we use to offer redress or compensation for past wrongs?

- What other issues in the news today should be the subject of redress or compensation?

Further Resources:

1. Ten short films about the Nikkei by students at Lucerne Secondary School, New Denver BC

https://tellingthestoriesofthenikkei.wordpress.com/category/films/

2. Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Centre, New Denver BC

http://centre.nikkeiplace.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/final_NI2012-Spring.pdf

3. Book: Dear Canada: Torn Apart: The Internment Diary of Mary Kobayashi, Vancouver, British Columbia, 1941 (Published 2012)

4. http://najc.ca/japanese-canadian-history/

Every effort has been made to gain permission from copyright holders to reproduce borrowed material. The publishers apologize for any errors and will be pleased to rectify them in subsequent reprints and website programming.

Educator Tools