|

Unit 4: Immigration, Migration, Refugees

Chapter 4: Chinese Immigration

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Educator Tools

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese Immigration: Timeline | |

|---|---|

| Dates | Events |

| 1858 |

|

| 1880-1885 |

|

| 1885 |

|

| 1900 |

|

| 1903 |

|

| 1907 |

|

| 1922 |

|

| 1923 |

|

| 1947 |

|

| 1957 |

|

| 1967 |

|

| 1984 |

|

| 1999 |

|

| 2006 |

|

| 2012 |

|

ACTION 1

Do

Creating a Visual Timeline

Each of the events highlighted in the timeline would have been reported by journalists throughout the country. Choose one of the events and create an illustration that might have appeared on the front page of the newspaper. What headline would accompany the illustration? You may choose to present your drawing in the form of a political cartoon.

Once completed, the class can arrange visual images in sequential order by creating a display or PowerPoint presentation.

ACTION 2

Do

Reporting events

Imagine that you are a journalist reporting on the event. What information would you offer your readers about the Chinese immigration experience? How might your report include the 5 W’s of reporting? Who? What? Where? When and Why? How does this event tell part of the story of immigration? What point of view might you use to present your article?

ACTION 3

Do

Responding to the Story of Chinese Immigration

Working in groups of three, record your reactions about a topic or issue and consider the views of others. Share your responses with two others to discover whether their opinions are similar or different from your opinion.

› Questions to Consider

- How did you react to the story of Chinese immigration? What surprised you?

- What are your opinions about any form of exclusion?

- Why do you think a federal government would discriminate in such a way? Was there any sound reasoning to imposing a head tax on the Chinese?

- Do you think apologies and payments are enough to compensate for the treatment of the Chinese?

› Take a blank piece of paper and fold it twice, to make four rectangles. Number the spaces #1, #2, #3, #4.

| #1 | #2 |

| #3 | #3 |

- In #1, write your response to one of the questions to consider connected to the issue of Chinese immigration. You might share your gut reaction, give an opinion, raise questions, or make a connection.

- Exchange papers with another person in the group. Read the response that is written in #1. Then, write your response to it in space #2. What did the response in space #1 invite you to think about?

- Repeat the activity one more time. Read both responses on the sheet you receive, and write a response to both in #3.

- The sheet is returned to the person who wrote the first response. Read all three responses on your sheet, and then write a new response in #4.

- As a follow up, the group can discuss the topic of Chinese immigration. Groups can share responses in a whole class discussion.

ACTION 4

Do

A Personal Response to Exclusion

A. Complete the following statements:

- For me, the word exclusion means . . .

- A story I know about exclusion is . . .

- One way to make up for an exclusion is . . .

B. Work in groups to share your responses. The following questions can guide your discussion:

- Is being excluded ever fair?

- Why might someone (or a group) exclude others?

- What does the story of exclusion of Chinese Immigrants remind you of – both personally and globally?

How Should Government Respond to a Past Injustice?

Key concepts › Redress

Key concepts › Redress

1. a. A relief from distress

1. b. A means or possibility of seeking a remedy

2. Compensation for a wrong or loss: reparation

Source: Merriam-Webster

Chinese Head Tax and Exclusion Act: Addressing the Issue of Redressing

After the Chinese Immigration Act was repealed in 1947, a number of activists, including Wong Foon Sien, began campaigning the federal government to seek redress for the head tax. But it took almost 60 years until an apology was offered. Why did it take so long?

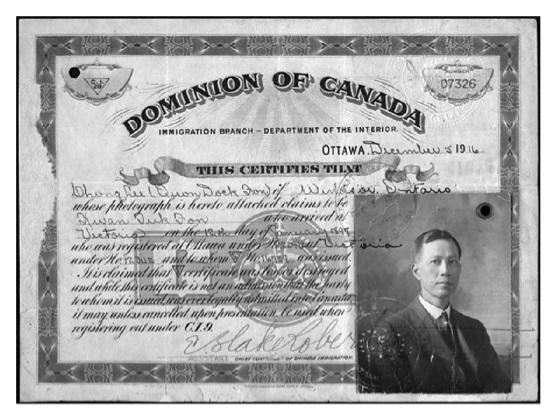

During the 1980s, over 4,000 head tax payers and their family members approached the Chinese Canadian National Council (CCNC) to register their head tax certificates. A redress campaign unfolded that included meetings, increased media profiles, research, publications and presentations in many communities. Although Prime Minister Brian Mulroney made an offer of individual medallions, a museum wing and other measures, these offers were rejected outright by the Chinese Canadian groups. In 1993, Jean Chretien’s cabinet openly refused to provide an apology or redress. The CCNC persevered raising the issue wherever they could, including a submission to the United Nations Human Rights Commission. In 2001, an Ontario court declared that the Canadian government had no obligation to redress the head tax levied on Chinese immigrants.

It was not until 2003, when Paul Martin was appointed prime minister, that there was a sense of urgency since there were only a few dozen surviving Chinese head tax payers. The issue continued to be a hot topic that was brought forth by politicians during federal elections. As part of his conservative party platform, Stephen Harper promised to work with the Chinese community on redress, a promise that he kept when elected in 2006. He stated, “Chinese Canadians are making an extraordinary impact on the building of our country. They’ve also made a significant historical contribution despite many obstacles . . . The Chinese community deserves an apology for the head tax and appropriate acknowledgement and redress.”

June 22, 2006—House of Commons

Finally, in a speech to the House of Commons on June 22, 2006, Prime Minister Stephen Harper offered an apology for the head tax. In his speech, Harper said, “We feel compelled to right this historic wrong for the simple reason it is the decent thing to do . . . a characteristic to be found at the core of the Canadian soul.”

Harper’s government offered symbolic payments of $20,000 to living head tax payers as well as to living spouses of deceased payers. Only an estimated 20 Chinese Canadians who paid the tax were still alive in 2006.

Funds were also established for community projects to educate Canadians about the impact of past wartime measures and restrictions.

Statements from the Calgary Chinese Culture Centre tell us how Chinese people reacted to the Harper apology.

Alex Louie, a Chinese veteran said, “All I ever wanted was an apology for the government to set the record straight.” Another early pioneer, Mary Mah, stated, “The sorrow and the hardship cannot be erased. But we can now begin to feel, in truth, I did not expect to see this, I don’t know about you, but I’m feeling very Canadian.”

Knowing that the Harper government extended an apology and compensation to the Chinese, we still need to consider whether an apology is enough (see unit three: The Komagata Maru). In order to fight against all forms of discrimination today, are we not obliged to keep alive the memory of past forms of discrimination? History is something that cannot be changed and a past injustice is not a wound that can be healed—or can it?

ACTION 5

Do

Writing a Position Paper

- What do you think can be learned from the Chinese Canadian experience?

- Do you think a group or the government owe a debt to someone for a past injustice?

For this activity you will have an opportunity to share your views on the concept of redressing an injustice. Write a position paper in which you support or oppose the responsibility of the Canadian government to apologize and respond in some manner to the wrongs committed by the governments of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

› Consider one or more of the following points that could be included in your paper.

- What would be considered a fair government response to victims and their children?

- What suggestions can you offer about how Canadians should best respond to the head tax?

- Does a government response to the Chinese set an unrealistic precedent for complaints for other injustices?

- How does a redress serve a useful social purpose? What is the best path to inclusion for all minority groups in Canada?

- What differences exist between our ideas of right and wrong in today’s society compared to those that existed in the past 100 years on the topic of immigration?

Every effort has been made to gain permission from copyright holders to reproduce borrowed material. The publishers apologize for any errors and will be pleased to rectify them in subsequent reprints and website programming.

Educator Tools