|

Unit 2: Genocide

Chapter 5: The Holodomor

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Educator Tools

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UKRAINIAN SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLIC | Year | RUSSIAN EMPIRE |

|---|---|---|

| Ukrainian National Republic | 1917 | Bolsheviks create the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic. |

| Ukraine declares a short-lived United Ukrainian National Republic by incorporating Western Ukrainian lands | 1919 | |

| Ukrainian nationalist forces unable to repel foreign aggression (Red Army, White Army, Poles, Entente); leaders forced into exile. | 1918 – 1921 | War; communism; bolshevik policy aims to establish a totalitarian socialist order; nationalizes all productive property; Cheka (secret police) and the bolshevik Red Army suppress worker and peasant uprisings. |

| Ukrainian lands divided up between four countries: Russia, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Romania. | 1921 | Red Army takes most of Ukrainian territory. A period of inflation, food rationing, forced labour and economic collapse ensues. |

| First Famine in Ukraine The expropriation of grain, a poor crop and severe food rationing during the civil war results in 1.5-2.0 million deaths by starvation in Ukraine. |

1921 – 1923 | The expropriated food is sent to feed Russian cities and the Red Army. |

Source: O. Subtelny, 2009. Ukraine: A History, Fourth ed. Toronto, 380-381.

| UKRAINIAN SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLIC | Year | RUSSIAN SOVIET FEDERATED SOCIALIST REPUBLIC |

|---|---|---|

| 1922 | Russia creates the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), including Russia, Ukraine, Belarus and Transcaucasia. Ultimate control, however, is in the hands of the Central Committee of the Communist Party in Moscow. | |

| In Ukraine, this policy is called ‘Ukrainization’ and results in a significant social, political, cultural renaissance, as well as the spread of a national consciousness. Source: P. Magocsi, 1996. A History of Ukraine, Toronto, 533-547 |

1923 | The USSR introduces a policy to recruit non-Russians into the Communist Party. |

| 1924 | Vladimir Lenin dies and a struggle for power sees Joseph Stalin take control of the Communist Party. Stalin aims to make all non-Russian republics into one single Russian communist state. He uses the OGPU, successor to Cheka secret police, to eliminate all internal opposition. Through terror, deportations, and executions, Stalin assumes complete control. | |

| Of the approximate 29 million people in Ukraine, 80% are ethnic Ukrainians and 89% of the farming sector is Ukrainian and demonstrates little desire for communist totalitarianism. | 1926 | Stalin fears that the peasant class, which owns agricultural land, is the social base of Ukrainian nationalism, and are thus, “enemies of the state.” |

| Collectivization meets with opposition from successful, wealthier, independent farmers. | 1928 | Stalin introduces the first Five Year Plan, a state imposed revolution from above, focused on rapid industrialization to modernize the USSR. He initiates forced total collectivization of agriculture (from private farms into state-owned) so the state can sell grain abroad and pay for industrialization. |

|

Stalin directs his secret police, the OGPU, to arrest Ukrainian political, intellectual, and religious leaders for allegedly belonging to a fictitious Union for the Liberation of Ukraine and conspiring for the separation of Ukraine from the USSR. Next, he liquidates the Ukrainian Autocephalous (autonomous) Orthodox Church, and sends bishops and priests to labour camps. Through executions, deportations or exile to the Gulag (Soviet prison camps), over 600,000 farmers and their families are liquidated, their property transferred to collective farms. Moscow sends in urban workers to expropriate property, organize collectives and supervise grain shipments; peasant uprisings are quelled by the regular army and OGPU units; any protesters are imprisoned or killed. Peasants slaughter farm animals in protest. |

1929 – 1931 |

Stalin regards Ukrainian nationalist tendencies as an impediment to building socialism. The Soviet state labels successful farmers as kulaks and “enemies of the state” and Stalin calls for the “liquidation of the kulaks as a class.” Stalin launches an attack on the remaining mass of farmers, most of whom oppose collectivization. |

|

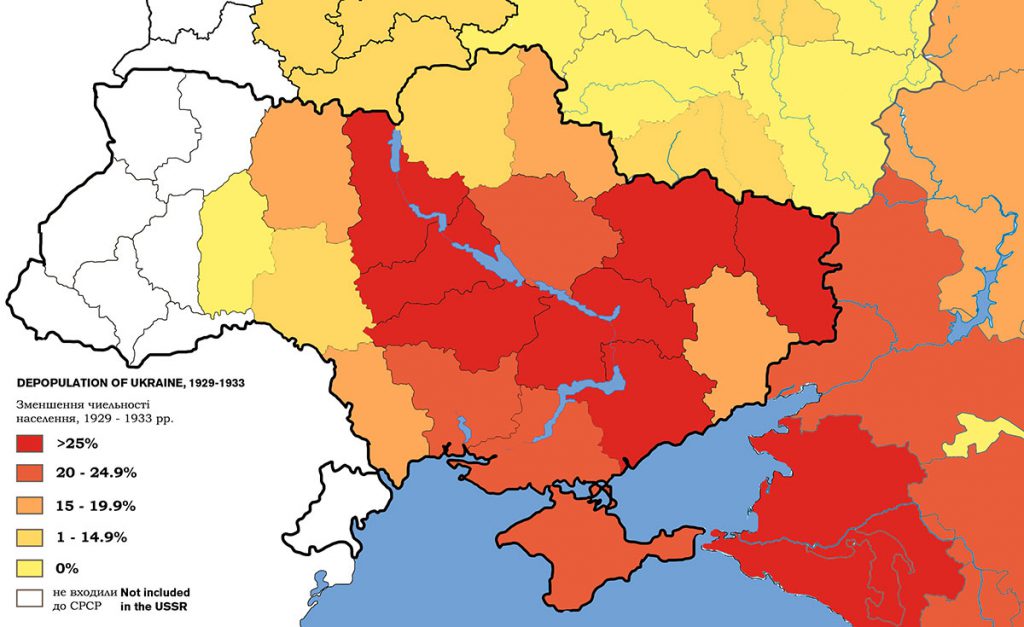

Famine spreads in Ukraine. There is not enough grain to meet government demands and to feed people. Many peasants flee collective farms, and seek food in towns and cities. The Ukrainian Communist Party pleads with Stalin to lower grain quotas. Famine (Holodomor) rages in Ukraine Swollen from hunger, desperate peasants eat rats, tree bark, and leaves to try to survive. Numerous cases of cannibalism are recorded. Demographers claim that at least four million men, women, children have starved to death in Ukraine as well as at least 600,000 deaths in the predominantly Ukrainian Kuban region. |

1932 |

The state creates penalties and policies making private farming economically impossible, sets unrealistically high grain quotas for collective farms, and demands they give up seed grain reserves. > August: Red Army units, OGPU secret police, and urban Russian communist activists act as enforcers. > November: > December |

|

In a meeting with Winston Churchill in 1942, Stalin admits to 10 million deaths during collectivization. During the spring and summer of June – July 1933:

Western governments, such as Great Britain, France, USA and Canada, are aware of the Holodomor but choose not to interfere in the “internal affairs of the USSR.” The Holodomor Legacy The famine provides a path to Soviet repopulation of areas where massive starvation occurred. Through the addition of Russian and other Soviet peoples into Ukraine and the dispersion of Ukrainians throughout the Soviet Union over several years, ethnic unity is destroyed and nationalities are mixed. |

1933. |

> January Stalin appoints Postyshev to speed up grain collection and to reprimand Ukrainian communists for failing to meet quotas. Some communists begin calling Stalin’s brutality in Ukraine genocidal. Postyshev’s gangs of activists conduct brutal house searches, tear up floors and walls looking for grain. Watchtowers are placed around farm fields; guards are directed to shoot anyone picking crops for food. At the height of this artificially-induced Famine (Holodomor), Stalin’s unrelenting drive to finance industrialization sees the Soviet government selling wheat to other countries at below-market prices. The Soviet government denies the Famine, and refuses help from international charitable organizations like the Red Cross. (Soviet propaganda and disinformation campaigns continue this denial into the 1980s) |

|

Ukrainian communist officials are replaced by Russian officials. Ukrainian cultural and political leaders are imprisoned or killed. Any spoken or written mention of the Holodomor is strictly forbidden and harshly punished. By Soviet policy, Russian is to become the language and culture of all of the peoples of the USSR. |

1933 – 1938 |

The Great Terror: |

|

The Ukrainian Communist Party declares the Famine was a “national tragedy,” but does not admit that is was genocide. |

1990 |

|

|

Ukraine declares its independence after the USSR dissolves. |

1991 |

|

| President Viktor Yushchenko, Ukraine’s first pro-Western leader, and the Ukrainian parliament recognize the Holodomor as a genocide. | 2006 |

Russian parliament passes a resolution denying that the Holodomor was a genocide. |

| Pro-Russian Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych rejects the Holodomor as a genocide. | 2010 | |

| Euromaidan (Revolution of Dignity) Massive public protests by Ukrainians, similar to those that took place on the Maidan in 2004, demand integration into Europe after President Yanukovych refuses to sign an association agreement with the European Union. Millions of people gather in Independence Square in Kyiv to protest corruption and human rights violations and eventually force President Yanukovych to flee the country. |

2014 |

Fearing a resurgence in Ukrainian nationalism, Russia annexes the Crimea and begins using hybrid warfare to destabilize Ukrainian sovereignty. |

| The Holodomor is presented as a genocide in history texts and is studied by students in Ukrainian schools. | 2015 |

The Kremlin continues to deny the Holodomor. |

Sources

Magocsi, P. 1996. A History of Ukraine, Toronto.

Klid, D. & Motyl, A. 2012. The Holodomor Reader, Toronto.

Hrushevsky, M., 1970. A History of Ukraine, Yale.

Hrushevsky, M., 1999. History of Ukraine-Rus’, Vol. 7, Edmonton, Toronto.

Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Kyivan Rus

Kuryliw, V., 2016. Holodomor in Ukraine

The timeline traces Russian imperialist aggression toward Ukraine beginning in the nineteenth century. You will notice that the Holodomor was one in a series of attempts by Russian imperialists and later Soviet authorities to dominate the land and people of Ukraine. However, the Holodomor was the most ruthless of all in that Stalin’s decrees created the conditions for genocide. As reports of starvation continued to surface, there was no compassion and no reversal of the plan. Stalin was determined to destroy Ukrainian citizens who openly defied communist ideology and collectivization within the USSR. The result was massive starvation of millions of men, women, children, and infants.

This engineered famine and tragic loss of millions of lives has slowly gained international recognition–Canada was the first western country to acknowledge the genocide. However, there are still many countries that do not officially recognize the events of 1932-1933 as a genocide created by the totalitarian regime of Joseph Stalin. Let’s take some time to examine primary and secondary sources of information.

Listen to an eyewitness account

Dying peasants on the streets of Kharkiv during the Famine-Genocide (1933 photo by A. Wienerberger)

Source: www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/

Artifact 1: Politburo Resolution on Grain Procurement in Ukraine

Artifact 1: Politburo Resolution on Grain Procurement in Ukraine

No.44 Resolution of the CC AUCP(b) Politburo on grain procurement in Ukraine

January 1, 1933

The CC CP(b)U and Ukrainian SSR RNK shall widely inform village councils, kolhosps, collective farmers and proletarian private farmers that:

Secretary, CC AUCP(b), J. Stalin

a) Those who hand in any grain that was previously misappropriated or concealed will not be subject to repressions;

b) Those collective farms, collective farmers and private farmers who stubbornly insist on misappropriating and concealing grain will be subject to the strictest punitive measures provided by the USSR Central Executuve Committee Resolution of August 7, 1932 “On the safekeeping of property of state enterprises, collective farms and cooperatives and strengthening public (socialist) property.”

RGASPI, fond 17, list 3, file 913, sheet 11.

CC AUCP (b) – Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolshevik) based in Moscow

CC CP (b) U – Central Committee of the Communist Party (Bolshevik) of Ukraine based in Kharkiv

RGASPI – Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History

Ukrainian SSR RNK – Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic Rada Narodnykh Komisariv (RNK), or Council of Peoples’ Commissars of the Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic

Source: Holodomor of 1932-33 in Ukraine: Documents and materials. Compiled by Ruslan Pyrih. Kyiv Mohyla Academy Publishing (2008), 77.

Artifact 2: Report from the Consul of Italy in Kharkiv

Artifact 2: Report from the Consul of Italy in Kharkiv

No. 67 Report from the Consul of Italy in Kharkiv to the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Italy on “Famine and Sanitary Conditions” (excerpt)

July 10, 1933

The current situation in Ukraine is horrific. Apart from larger towns and raions within a fifty kilometer radius of cities, the country is engulfed in famine, typhus and dysentery. There are also cases of cholera and even plague which until recently were sporadic. […]

The famine has decimated half the rural population.

Police apprehend fleeing peasants with livid brutality (I have noticed that the urban population willingly takes part in this hunt for villagers, either because of some incomprehensible feeling of self-defence, or under the influence of crafty propaganda, or an overwhelming desire to commit torture). If somebody tries to escape from the police transports, there are always a dozen city residents prepared to chase him down, beat him up and turn him over to the police. There are orders prohibiting doctors from administering medical treatment to villagers in the cities.

Two thousand such poor souls are rounded up every day and shipped out during the night. Entire families, that came to the city in the last hope of avoiding death from starvation, are held in barracks for one or two days and then transported, hungry, 50 kilometers from Kharkiv and thrown into rain-formed gullies.

Many of them that can no longer move and simply die on the spot; some manage to escape and others are fortunate enough to make it back to the city where they end up begging for food. One of them told me about an area located between the ponds beyond Rai-Yelenivka, a four-hour walk away from nearest railway station. Every three to four days, a team of gravediggers is dispatched there to bury the dead.

Some doctors whom I know confirmed that death rates in the villages often reach 80 percent, but never less than 50 percent. Kyiv, Poltava and Sumy oblasts were most afflicted by the famine and can be described as depopulated.

I am adding another name to the list of dead villages: Lutova near Kharkiv. Prior to the famine its population was 1,500. Today it is just under 90.

As for sanitary conditions, they can be no worse than their current state. Doctors are prohibited from speaking about typhus and death from starvation. They are also prohibited from compiling statistics that may be interesting from the scientific point of view. Nonetheless, I was able to obtain the following information about pathologies due to undernourishment. People who are unable to secure bread (very black bread with various additives) gradually grow weaker and die of heart failure without any signs of disease. Meanwhile, those who consume only fluids and milk experience swelling of their joints and legs. They also die from heart failure.

Source: Holodomor of 1932-33 in Ukraine: Documents and materials. Compiled by Ruslan Pyrih. Kyiv Mohyla Academy Publishing (2008), 114-115.

Artifact 3 – Population Figures

Artifact 3 – Population Figures

Population Figures for the East Slavic Nationalities and the USSR as a Whole

| Taken from: The Great Famine in Ukraine: The Unknown Holocaust. Published by the Ukrainian National Association, p. 33. The source of information is “Natsionalisti SSR” by Kozlov, p. 29. Small Soviet Encyclopedia, 1940 edition, under “U” – “Ukrainian SSR”; Ukraine’s population in 1927 census listed at 32 million; in 1939 (twelve years later) – 28 million. |

||||||

| 1926 | 1939 | % Change | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | % | Population | % | |||

| USSR | 137,397,000 | 100.0 | 170,557,100 | 100.0 | +16.0 | |

| Russians | 77,791,001 | 54.0 | 99,591,500 | 54.0 | +28.0 | |

| Byelorussians | 4,738,900 | 3.3 | 5,275,400 | 3.1 | +11.3 | |

| Ukrainians | 31,195,000 | 21.6 | 28,111,000 | 16.5 | -9.9 | |

Number of Children Attending Schools

| Source: Cultural Construction of the USSR, Moscow: Government Planning Pub., 1940, pages 40-50. Charts reprinted from the Genocide Never Again Workbook. Used with permission. | |||

| Dates | Russian SFSR | Ukraine | Byelorussia |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1914-1915 | 4,965,318 | 1,492,878 | 235,065 |

| 1928-1929 | 5,997,980 | 1,585,814 | 369,684 |

| 1938-1939 | 7,663,669 | 985,598 | 358,507 |

Artifact 4 – Resettlement Directives

Artifact 4 – Resettlement Directives

No. 68 Resolution of the USSR SNK on resettlement to Kuban, Terek and Ukraine

August 31, 1933

Chairman, USSR Council of Peoples’ Commissars,

The Council of People’s Commissars of the Union of SSR resolves:

The All-Union Resettlement Committee of the Council of Peoples’ Commissars of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics shall organize the resettlement of 10,000 families to Kuban and Terek, and 15,000-20,000 families to Ukraine (Steppe) by the beginning of 1934.

V. Molotov (Skryabin)

Executive Director, USSR Council of Peoples’ Commissars,

I. Miroshnikov

No. 69 Resolution of the CC CP(b)U Politboro on additional resettlement of Steppe raions (excerpt)

September 11, 1933

Prepare the following numbers of additional resettlements to the Steppe raions during the fourth quarter of 1933: 22,000 families to Dnipropetrovsk, 9,000 families to Odesa and 4,000 families to Donetsk oblasts.

Recruit additional resettlers from among those collective farmers, laborers and private farmers who are willing to join the collective farms of the Steppe.

Establish the following recruitment targets: 8,000 families each from Kyiv and Chernihiv oblasts and 6,000 families from Vinnytsia oblast.

Conduct additional resettlement to Dnipropetrovsk oblast from Kyiv and Chernihiv oblasts, to Odesa oblast from Vinnytsia and Kyiv oblasts, and to Donetsk from Chernihiv oblast. […]

SNK – Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR (Soviet Narodnyhkh Komisariv)

CC CP (b) U – Central Committee of the Communist Party (Bolshevik) of Ukraine based in Kharkiv

Source: Holodomor of 1932-33 in Ukraine: Documents and materials. Compiled by Ruslan Pyrih. Kyiv Mohyla Academy Publishing (2008), 116-117.

Artifact 5: International Recognition of Holodomor

Artifact 5: International Recognition of Holodomor

Canada recognizes the Holodomor as an act of genocide against the Ukrainian people. In addition to Canada, other countries who recognize the Holodomor are:

- Argentina

- Australia

- Colombia

- Czech Republic

- Estonia

- Ecuador

- Georgia

- Hungary

- Latvia

- Lithuania

- Mexico

- Paraguay

- Peru

- Poland

- Portugal

- Slovak Republic

- Ukraine

- USA

- Vatican

Canada Remembers Holodomor Victims

In 2003, the United Nations (UN) and delegations from 25 countries issued a Joint Statement on the Great Famine of 1932-1933 in Ukraine (Holodomor). The opening statement reads as follows:

In the former Soviet Union millions of men, women and children fell victims to the cruel actions and policies of the totalitarian regime. The Great Famine of 1932-1933 in Ukraine (Holodomor), which took from 7 million to 10 million innocent lives, became a national tragedy for the Ukrainian people. [Correction: today, the scholarly consensus put the number of victims at 3.9 million.]

While the UN considers the Holodomor a national tragedy, they fall short of using the term genocide. In 1990, the UN International Commission of Inquiry into the 1932-1933 Famine in Ukraine (Geneva) concluded that the Famine in Ukraine was in fact a genocide. At the same time, the Commission could not confirm that the Moscow authorities had a preconceived plan to organize a famine in Ukraine. The only dissenting opinion came from Professor Sundberg, the head of the commission, who concluded that: “the evidence shows that the famine situation was well-known in Moscow from the bottom to the top. Very little or nothing was done to provide some relief to the starving masses. On the contrary, a great deal was done to deny the famine, to make it invisible to visitors, and to prevent relief being brought.”

Artifact 6 – An Author’s Chronicle of Events

Artifact 6 – An Author’s Chronicle of Events

Following an unofficial trip to Ukraine in 1933, journalist Gareth Jones shared his stories of government oppression and famine with George Orwell, a young British author. Years later, Orwell wrote the novel Animal Farm in which he satirized the corrosive effects of communism. He also alluded to an artificial famine and the need to conceal it from the outside world in chapter seven of his novel.

“For days at a time the animals had nothing to eat but chaff and mangels. Starvation seemed to stare them in the face. It was vitally necessary to conceal this fact from the outside world. Emboldened by the collapse of the windmill, the human beings were inventing fresh lies about Animal Farm. Once again it was being put about that all the animals were dying of famine and disease, and that they were continually fighting among themselves and had resorted to cannibalism and infanticide. Napoleon was well aware of the bad results that might follow if the real facts of the food situation were known, and he decided to make use of Mr. Whymper to spread a contrary impression.”

Orwell created a different preface to his novel in an underground Ukrainian edition of Animal Farm that was published in 1947. The translated edition was circulated throughout displaced persons’ camps in Europe following World War II.

Artifact 7 – Intergenerational Impact of the Holodomor

Artifact 7 – Intergenerational Impact of the Holodomor

Researchers have found that collective trauma is passed down from generation to generation, a phenomenon known as intergenerational trauma. In Canada, the impact of intergenerational trauma has been highlighted by survivors of residential schools. It is what happens “when untreated trauma-related stress experienced by survivors is passed on to second and subsequent generations. The trauma inflicted by residential schools and the Sixties Scoop was significant, and the scope of the damage these events wrought wouldn’t be truly understood until years later.”

A research study by Brent Bezo and Stefania Maggi (The Intergenerational Impact of the Holodomor Genocide on Gender Roles, Expectations, and Performance: The Ukrainian Experience, 2015) investigated how three consecutive generations perceived the impact of the Holodomor on their lives in modern-day Ukraine. The findings indicate that:

“intergenerational trauma, stemming from the Holodomor genocide, continues to exert its effect through gender-specific impacts. These impacts seem to occur at the individual level, in terms of affecting well-being and behaviours. The participant reports also suggest that collective trauma has a long-term, intergenerational impact on how men and women view themselves and each other, in a broader sense and in relation to gender roles, expectations, and performance. In this respect, participants did not only refer to themselves or known individuals in their own personal environments, but also spoke about a wider impact affecting the greater Ukrainian context. As such, our results suggest that the Holodomor had an impact at the societal level. This result reflects an area that has not been extensively studied and has yet to be well understood, but is consistent with the view that collective traumas play a critical role in shaping socio-cultural norms and values beyond the individual level. The impact of genocides at the societal level has implications for how interventions may address the healing of collective trauma and its intergenerational transmission, which may require the application of multi-level frameworks. Specifically, our results suggest that the healing of collective trauma also requires an understanding of gender-related impacts, in that victimization of men via gendercide might also result in a hidden or less overt intergenerational victimization of women. Hence, the historical roots of collective trauma should be considered for healing its intergenerational impacts.” (3-4)

The Press – Facts versus Fake News

Previously sealed files from the Soviet era are now available to historians and researchers. Many of the documents from the files provide compelling evidence of a government-imposed famine, with losses of 3.9 million people in the Ukrainian lands and 1.1 million in the grain-growing regions of Soviet Russia and Kazakhstan.

Unfortunately, in 1932-1933 evidence of the famine was kept well-hidden. Journalists were rarely allowed into Ukraine due to a travel ban. At least three noteworthy journalists did manage to travel to the region, one with the permission of Soviet authorities, and two who ignored the travel ban. The articles they wrote convey divergent views.

Read the article written by Ian Hunter titled “A Tale of Truth and Two Journalists.” Study the summary of interpretations offered in the chart and examine the articles published by both Malcolm Muggeridge and Walter Duranty (links given) to gain greater insight into each interpretation.

Note: Duranty’s article was written in response to the eyewitness accounts of journalist Gareth Jones. Walter Duranty travelled with the permission of Soviet authorities. Malcolm Muggeridge and Gareth Jones ignored the travel ban and went on their own.

| Genocide Believer: Malcolm Muggeridge | Genocide Denier: Walter Duranty |

|---|---|

|

|

The University of Alberta’s Holodomor Research and Education Consortium offers some reasons for the lack of awareness by the public about the artificial Famine of 1932-1933. It is interesting to note that even though many detailed accounts of the Holodomor were written, Duranty’s articles, which were backed by Soviet authorities, overshadowed the work of other journalists.

ACTION 1

Discuss

- Why was the Holodomor denied for so long and what ended the controversy?

- Can historical facts be denied when there is archival proof? Consider other examples of genocide denial such as Holocaust denial and denial of the Armenian genocide.

Write your answers and then discuss as a class.

ACTION 2

Do

Why is it that the earliest accounts of the Holodomor originated from diaspora Ukrainians and not from survivors living within Ukraine?

Write your answer and then discuss and compare with a partner in class.

ACTION 3

Do

Although the Holodomor of 1932-1933 is now widely recognized (see Artifact 5), Canada prides itself on being the first country in the world to declare that the Soviet engineered famine was a genocide against the Ukrainian people.

The Senate calls upon the Government of Canada “to recognize the Ukrainian Famine/Genocide of 1932-1933 and to condemn any attempt to deny or distort this historical truth as being anything less than genocide.” June 17, 2003.

In 2008, a private members’ bill was introduced to establish a day of remembrance for the Holodomor, Ukrainian Famine and Genocide (“Holodomor”) Memorial Day.

- Read about the introduction of Bill C-459. Which speaker, in your view, had the most compelling presentation?

- Select and record six pieces of information about the Holodomor that were shared by the speakers and captured your attention.

- Discuss as a class: Why is it important to recognize the Holodomor as a genocide?

- Are there other examples of historic injustices recognized by Canada’s parliament? Work in pairs to research and record your answers.

ACTION 4

Discuss

After viewing Artifacts 1, 2, and 3, reflect on the following questions:

- Statistical data and documents from the years 1932-1933 were released to the public following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Given these new sources of evidence, do you think that the integrity of journalists such as Malcolm Muggeridge and Gareth Jones will be restored? Explain your reasoning.

- Create a five-minute presentation to the Pulitzer Prize committee about Walter Duranty’s award, and present it to your class.

ACTION 5

Think

A. Holodomor survivors who escaped to countries such as Canada have shared eyewitness accounts of cruelty and starvation in Ukraine during 1932-1933.

- There was no mention of the artificial famine, the Holodomor, in school textbooks in the Soviet Union, including Ukraine. Reflect on why this information was left out of the school curriculum.

- Germany has set an example by recognizing the crimes of Nazi Germany and trying to come to terms with this history. Reflect on the political, cultural, educational, economic, and geographic implications for Russia if government authorities were to accept responsibility for the Holodomor.

B. The next question refers to George Orwell’s Animal Farm. If you have read it, please proceed.

Andrea Chalupa has researched Orwell’s introduction to the Ukrainian version of Animal Farm (see Artifact 6). She speaks of the “revived revolutionary spirit” among displaced persons (DPs) upon reading this satire about communism, collective farms, and famine. Do you think that Orwell’s book motivated Ukrainian survivors to share their recollections of the Holodomor in the diaspora? Why or why not?

ACTION 6

Do

Artifact 7 explores intergenerational trauma. Define the following terms related to the history of residential schools in Canada: colonization, mistrust, indigenous inhabitants, cultural genocide, intergenerational trauma, and resettlement.

- Using your definitions, work with a partner to draw parallels and contrasts between residential schools and the Holodomor.

- Is it ever acceptable to compromise human rights to build a nation? Reflect on this topic and record your answers. Make a presentation to classmates, with a clear explanation of your views.

The Holodomor and the Great Leap Forward in China

Twenty-five years after Stalin’s Holodomor, General Mao Zedong launched the “Great Leap Forward” in 1958. Both communist leaders wielded apparently unlimited power in their efforts to eliminate private farms and promote rapid industrialization. According to an expert on the subject, historian Frank Dikötter, Mao’s policies precipitated mass famine, rampant cannibalism, causing an estimated 30 million deaths.

Dikötter, Frank – Mao’s Great Leap to Famine. International Herald Tribune. December 15, 2010

ACTION 7

Do

A. Select 10 adult participants for a history survey. First thank them for participating and let them know they will be identified only by number with no names recorded.

B. Question for them:

What do you know about the Holodomor and the Great Leap Forward?

C. Give them scores out of a total of 5 based on correct answers to:

Where? When? What? Who? Why?

- (Where) know that Holodomor refers to the Ukrainian genocide and the Great Leap Forward was a Chinese genocide.

- (When) provide dates (1932-1933 Holodomor; 1958-1962 GLF) or in the correct decade.

- (What) express a rough approximation of the number of man-made deaths attributed to the Holodomor (3.9 million) and the Great Leap Forward (30 million).

- (Who) know that General Mao was behind the GLF and Stalin was behind Holodomor.

- (Why) know that both famine-genocides were created by communists who wanted to eliminate private farms and rapidly increase industrialization.

D. Participants may be asked to volunteer their level of education and how they learned about these genocides.

E. Analyze your results as individuals and then as a class looking at trends and the potential explanations of those trends.

Every effort has been made to gain permission from copyright holders to reproduce borrowed material. The publishers apologize for any errors and will be pleased to rectify them in subsequent reprints and website programming.

Educator Tools